This is probably going to be the first of at least two posts about the response to the Moore-Burchill article and fallout. In this one, I want to talk about the term “cis” and objections to it, and in a future post I want to talk about the media framing. There might be some other stuff if anything strikes me.

One of the fascinating (for me at least) things about the ongoing Moore-Burchill thing is the issues of language, identity and power. There’s a real tussle over words – hate speech, slurs, violence, identity. A lot of it is to do with who gets to use which words.

Firstly, objections to the word “cis”.

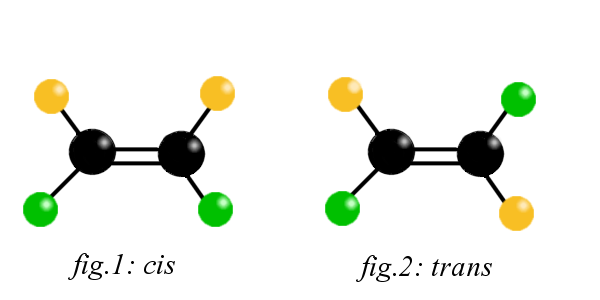

I have to admit that I’m hiding a dark and shameful secret here: I have an A-level in Chemistry. Not a good one, but it meant that I first came across cis and trans when talking about isomers. Basically, an isomer has a carbon double bond in the middle which means it can’t rotate on that axis. This means that the molecules attached to the carbon atoms can’t swing around. It’s actually a really nice illustration, so have a very quick diagram (and don’t laugh at my lack of artistic skill).

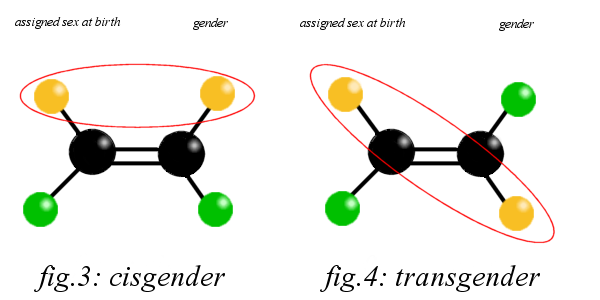

As you can see in the cis isomer in figure 1, the yellow molecules are on the same side and the green molecules are on the same side. And that’s all cis means: “on the same side”. In the trans isomer in figure 2, the yellow molecules are across from one another, as are the green molecules. And that’s all that trans means: “on the other side” or “across”.When we talk about gender, we use cis to describe people whose assigned sex and gender identity are in alignment and trans to describe people whose assigned sex and gender identity aren’t in alignment. The diagram below shows this:

Obviously this isn’t (and cannot be) a perfect representation of the complex relationship between assigned sex at birth and gender identity, but it will do as a starting point and hopefully makes things clearer.Cis is simply trying to give a name to a certain set of experiences. Actually being able to put a name to this set of experiences is important. The term is not an insult or a term of derision.

One of the problems here is that there are words to describe minority experiences but not necessary words to describe majority experiences. If we don’t have words for majority experiences, it makes them even more pervasive and normalised. For example, if we don’t have words to describe white people or heterosexual people or able-bodied people, then people who are not these things exist as a marked experience – as something unusual or Other. Many feminists quite rightly object to terms like “lady doctor” or “female doctor” because it assumes that doctors are male, and any deviance has to be carefully noted and expressed. My mum, a doctor, once made a home visit accompanied by a nurse. When she got there, she was taken aback to find that the nurse was being addressed as the doctor – because he happened to be male. The assumption was that if there’s a doctor and a nurse and one of them happens to be a man and the other a woman, then the man is the doctor and the woman is the nurse. Prejudices like this are reinforced by gender marked terms like “lady doctor” or “woman police constable”.

Similarly, if a white person said “I don’t like being called white, I’m just a normal person” I’d be annoyed because that suggests that their white experience is the default – that normal people are white, and that non-white people are somehow not normal. There’s an additional dynamic at work with people who say “I don’t like being called cis, I’m just a normal woman” because it actively positions normal women as those who were assigned female at birth and in doing so, rejects that trans woman can also be “normal women”. While I’m sure some objectors genuinely do reject trans woman as women, I’m also confident that many more simply haven’t thought about their use of language and are unaware of the implications. There is nothing bad about being described as “cis” just as there’s nothing bad about being described as “white” or as “able-bodied”. It just means giving a name to the majority experience and in doing so, shifts it away from being the default experience.

As a linguist, I also find Julie Burchill’s objection to cis as “sounds like syph, cyst, cistern” kind of hilarious. As Tony McEnery notes, “the sounds in a word such as shit seem no more unusual, and combine together in ways no more interesting, than those in shot, ship or sit“; just because a word sounds a bit like other words doesn’t mean it has anything to do with them in terms of meaning.

As a pedant with access to the Oxford English Dictionary (a dangerous combination), I note that syph is an abbreviation of syphilis, itself apparently derived from “Syphilus, the name of a shepherd in the poem Syphilis, sive Morbvs Gallicvs (‘Syphilis, or the French disease’), supposedly the first sufferer from the disease. Cyst is derived from cystis from the Greek κύστις, meaning “bladder”. And cistern is derived, through the Old French cisterne, from the Latin cisterna, meaning “a subterraneous reservoir”. While these words sound similar, they have very different origins, histories and usages. It’s rather disingenuous to take offence at a word simply because it sounds like another word that means something unpleasant.

To reinforce my point, I note that the Guardian/Observer Comment is Free section is often referred to with an acronym: Cif. Which also happens to be a popular brand of bathroom cleaner. Isn’t the arbitrariness of language great?

References:

McEnery, T. (2006) Swearing in English: Bad language, purity and power from 1586 to the present. London: Routledge