I grew up in a medieval city, its Anglo-Saxon quarters still somewhat in evidence and traces of its inhabitants and their trades and their prejudices echoed still in the street names. The city itself is a palimpsest, post-war layered on Victorian layered on Georgian layered on Tudor layered on medieval layered on Anglo-Saxon and, crouching in alcoves, the city’s old Roman walls. It’s impossible to live there and not let that somehow soak into your bones, just a quiet awareness that your life is one breath against the city’s dreaming stones.

And yet, all of this history is just part of your life. When you grow up playing on castle ruins (destroyed in the English Civil War and never rebuilt) and running around a medieval great hall and there are Roman coins on a table in your primary school because they were dug up in someone’s dad’s field, and you spend your teenage years perched on tombs and ruining tourists’ photos by sprawling messily on the market cross, it’s impossible to be too reverent about the history that surrounds you. As a child, I was enchanted by illuminated manuscripts – and also by the graffiti carved into the cathedral stones. History is real people, real lives – not just stuff to distantly admire.

I hope that this came across in my teaching as I offered them historical context along with linguistics, information about Anglo-Saxon farming methods taught alongside the case system. I wanted them to understand where these texts came from – the fact that manuscripts were heavily used, the physicality of operating a heavy printing press.

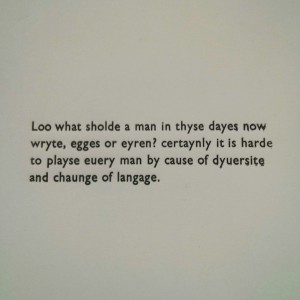

Happily, the university has a massive school of art and one of their specialities is various forms of printing, so off we went to operate a letterpress. Our guide to the process, Naomi Midgley, showed us around the typecase, how to set up a composing stick and had prepared a forme of a text for us to print. Because I couldn’t resist trolling my students a little bit, I chose a extract of Caxton. Then we got to place the forme in the press, ink it, carefully place a sheet of paper over it, place the tympan and frisket over it, roll the coffin into place, pull the bar towards us to lower the platen then push it to raise it, then roll the coffin back out, lift the tympan and frisket and finally lift the sheet of paper to view the new print. It was an important insight into the physical nature of producing a print and what can go wrong as our inexpert hands applied too much ink, not enough ink, applied too much pressre from the platen, not enough pressure, nudged the paper as we lifted it off and smudged the wet ink. It was one thing to read about the process of producing a printed text; quite another to actually do the labour myself. If I could, I would love to apprentice myself to a printer, to learn how to reach into the the typecase without having to look, to assemble formes, to allow the process of operating a press mark my body with ink and callouses and changed musculature.

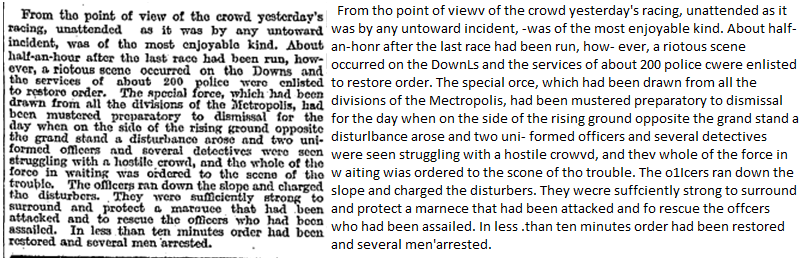

As a corpus linguist, one of the things I struggle with is the way that materiality is both present and absent in the texts I use. I use large collections of machine-readable texts, stored on my computer or a server and manipulated using a computer program. I don’t go into archives, rarely physically come into contact with my texts. However, they are scanned using Optical Character Recognition and through this, the early twentieth century newspaper texts I use with constantly remind me of their physicality.

In these texts, flecks of dirt or ink, smudges, imperfections in the paper and so on are interpreted as salient by the OCR program: spots of dirt or ink become full stops or commas or dashes or part of a colon or semi-colon, flecks of ink mean that o acquires a tail and becomes a p or q or b or d, smudges turn a c into an o or an e and so on. In corpus linguistics the text is both isolated from the way it was physically produced, yet the method of production haunts the text, is a ghost (or perhaps a poltergeist) in my analysis. I often had to return to images of the newspaper text to interpret my concordance lines or manually correct texts for detailed analysis.

I don’t have an easy answer or, indeed, a conclusion. Perhaps all I can do is suggest what I had to do so many times when the smudges and blobs became too much: return to the text with human senses.