I’ve been discussing intersectionality elsewhere, so thought I’d edit those comments into a post here. I came to this concept though my activist communities rather than academia, and as such, that’s the language I use here. At the end of the post I’ve put a couple of links to posts about intersectionality that I found particularly helpful.

Basically, “intersectionality” means acknowledging our various experiences, often in terms of privilege, and how these affect each other. It takes as a starting point that we have different experiences and that these experiences influence and intersect with each other. If we have a particular experience – for example, being white – we experience the world as a white person. This risks blinding us to the experiences and issues faced by people who aren’t white.

Think of it as getting dealt a hand of cards. You have cards for race, assigned sex at birth, sexuality, trans-cis identity, (dis)ability, class, education, immigrant status and so on. A few people get absolutely shitty hands and a few people have absolutely amazing hands. Most of us are in the middle – we have a good card or two and a shitty card or two and some others in the middle.

So, for example, someone might have cards for “white”, “cis”, “male” and “heterosexual” but a shitty card for “wealth”. What intersectionality means is that this hypothetical man experiences his whiteness, cis-ness, masculinity and heterosexuality differently than someone who has those cards but has a good card for wealth – his lack of wealth affects these things in different ways. However, he also has a different experience from someone who has the same shitty wealth card but who also has a woman/queer/non-white/disabled card. Intersectionality can account for complex situations, like poor white men and rich Black women, and help us understand that privilege doesn’t occur along simple axes. It can also help identify areas where people experience multiple oppressions.

As an example, say a company decides to sack all its non-white women workers. Technically, they aren’t being racist – after all, they’re still employing non-white men. And technically they aren’t being sexist – after all, they’re still employing white women. However, people who exist in the middle of those intersections are being discriminated against.

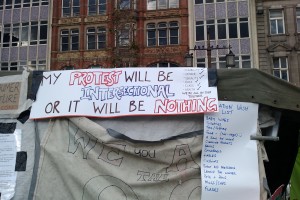

A fairly common experience for intersectional feminists is to encounter white, cis, middle-class, able-bodied feminists are telling them that they should be focusing on their particular interpretation of feminism and leaving race, class, disability, trans* experiences etc out of it. To draw a parallel, it’s a bit like being told by lefties that “you can have feminism after the revolution” or “how dare you accuse us of sexism, it distracts from class war”.

doing intersectionality

The issue for me is not putting aside difference, but how to react when faced with them – and especially how to react when you’re part of the system that unthinkingly perpetuates such hierarchies.

For example, I don’t identify as disabled. I am unaware of what it’s like to navigate society as a disabled person, and if I’m not careful I can unintentionally hurt people.

What I do try to do is be aware of access issues, never speak on behalf of people with disabilities if someone who actually experiences such issues is willing to speak, amplify their voices (whether this be through promoting their writing/events/activism or literally handing someone the mic and them speaking rather than me), listen and learn, and learn the etiquette. If I can help without talking over someone or denying them their voice I will do so – for example, in tutor training sessions I’ve pointed out access issues because no one else did. But basically, I take my lead from them.

I don’t get this right all the time. I make mistakes and I am called on them. However, when this happens, I apologise immediately and I try to always take the criticism on board and change my behaviour in light of it. When I am criticised it’s often not particularly personal; it’s because I’ve blundered into something or screwed up, and so embodied something that hurts people with disabilities. There’s a balance between being systematically unaware of issues because you don’t experience them and using that as an excuse to not learn and educate yourself.

Whether or not I am a disability ally is not my decision to make – I don’t get to decide whether I am or not. I’ve encountered too many people who call themselves white allies but behave in really problematic ways. Instead I try to behave in a way that supports that group of people without Making It All About Me.

why intersectionality matters

I am someone who lives in the intersections. In some ways I am enormously privileged – I am highly educated, when I was growing up my parents could afford books and they encouraged and valued my education. In other ways, I am far less so. Intersectionality is the only framework I’ve found that can make sense of these experiences.

Living in such intersections means you can have no heroes. People who are good on trans* issues can disappoint you when it comes to race; people good on race issues can disappoint you when it comes to sexuality; people good on LGBQIA issues can disappoint you when it comes to disability issues.

As an activist, there are are lefty groups that I won’t go near because of their racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia. I feel unwelcome and unsafe in those spaces, and I’m not risking verbal (and potentially physical) abuse to engage with them. As a child, I never saw people in the news or on TV or in books who were like me. As a student, I have never been taught by someone with a non-European non-white background – and when I teach, I am incredibly aware that this may have been the case for my students. I am constantly aware of being the only minority in some way in almost any group I’m in. I am constantly aware that no space is completely safe for me. For me, interesctionality is a real, visceral thing.

As a thinker and an activist, I deeply appreciate the nuances intersectionality can offer. For example, when Burchill writes about trans* people and their “big swinging PhDs” – so arguing that only non-working class, highly educated people are trans* – did she stop to think that a working class, non-university educated trans* person would experience all the discriminations and challenges of being working-class and non-university educated trying to establish a journalistic or otherwise highly visible career AND the discriminations and challenges of being trans* and trying to establish such a career, plus a few more? If you didn’t have money – but if you did, you’d be forced to choose between funding internships or going private for the treatment the NHS denies you? That is an incredibly hard place to be.

further responses to Moore/Burchill

Quinnae Moongazer – Unguarded and Poorly Observed: A Response to Julie Burchill

Christine Burns – Mending Fences

Paris Lees – An open letter to Suzanne Moore

Roz Kaveney – Julie Burchill has ended up bullying the trans community

CN Lester – The Julie Burchill transphobia scandal

Ruth Pearce – Transphobia in The Guardian: no excuse for hate speech

Ariel Silvera – Targeting trans women, or the pathetic pastime of increasingly irrelevant wealthy people

Hel Gurney – More on Moore, Burchill, and hate speech

Grace Petrie – Comment Is Free, to attack trans people

Laurie Penny – On feminism, transphobia and free speech

further reading on media representation of trans people and issues

Juliet Jacques – A Transgender Journey: how it came about

further reading on intersectionality

Catherine Baker – On intersectionality, academic language, and where to put my big feet

Sophie Cansdale – The Pitfalls of Privilege: OWS, Social Justice, Intersectionality

Flavia Dzodan – My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit!