This is my contribution to a roundtable discussion on trans and non-binary activism at Sexual Cultures 2: Activism meets academia. My co-panellists were Ruth Pearce, Jade Fernandez and Dr Jay Stewart and the facilitator was Dr Meg John Barker.

____

Today I’m basically going to argue that academia and activism inform and enrich each other. There are commonalities between the two: both engage with the world around us, both describe it and seek to understand it. Both ask – and respond – to difficult questions. However, there are also differences: activism explicitly seeks change whereas not all academic work does so. Activism can also take many different forms, and there are different barriers to enter it[1].

Both my academic research and activism are interested in people – how they form the identities they have, how they communicate these and make them legible, how they understand themselves, how they challenge the societies they live in.

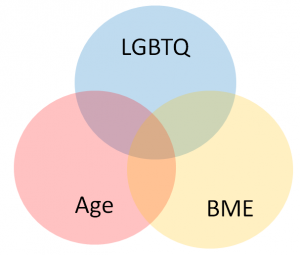

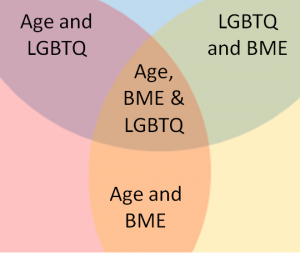

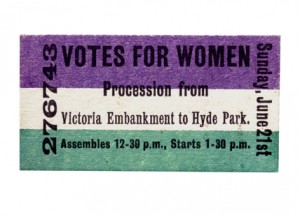

My academic work has focused on the newspaper representation of the suffrage movement and, more recently, how trans people are represented in the media. Representation is crucial to changing perceptions of minority and/or disadvantaged groups – it is how people who may never meet us and interact with us learn about us. As my research on the suffrage movement shows, mainstream media representation can over simplify complex issues and debates, conflate identities, and focus on things like property damage to the exclusion of decades of non-violent direct action – all of these are pretty damaging to already disadvantaged groups. We can see this focus on accurate media representation in trans activism through projects like Trans Media Watch and All About Trans. I’ve also found myself contributing to discussions on Black and Minority Ethnic LGBTQ elders and have had difficult experiences at conferences when my intersectional identity means I am seen as the subject of someone else’s research rather than a researcher in my own right.

Academic work allows us to gather, interpret and analyse data. In my field of corpus linguistics, we talk a lot about rigour – can these results be replicated? are they statistically valid? how can I be sure that the things I find are actually there and not simply a case of overextrapolation? These things are necessary to talk about in activism too – how do I know there is a problem? is it systematic? who does it affect? how does it affect them? This is especially important in a context of funding cuts and pressure on services. I’m sure that I am not the only person to have been asked whether there is a demonstrated need for services that support trans, and especially nonbinary, people. There’s a vicious cycle at work where we don’t know exactly how many trans people or nonbinary people there are because surveys rarely ask the right questions to get decent answers, so it’s hard to get changes made that will help us and increase our visibility, so it’s harder for trans and nonbinary people to make their identities clear and be counted.

Nat Titman notes that “Reliable figures show that at least 0.4% of the UK population defines as nonbinary when given a 3-way choice in terms of female, male or another description” before going on to observe that “If gender is asked in terms of frequency of feeling like a man, a women, both or neither then there is evidence that more than a third of everyone may experience gender in a way that defies binary categories”. Nat argues that “If you wish to measure the numbers of people who don’t fit within binary classifications of female/male or man/woman then your choice of question will have a huge effect on the results […] Asking for ‘Other’ in the context of ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ is likely to reduce the number of people identifying outside of the binary to the lowest possible figure, those who feel strongly enough to reject classification with binary ‘sex’ as well as the man/woman binary”.

As Nat makes clear, there is a need for more research in this area – and designing the kind of surveys that can be sensitive to this kind of information is something that academics and activists can work on together.

On a more personal note, my undergraduate essays were possibly an extremely awkward and nerdy coming out process. My first introduction to gender as more complicated than a binary and ideas about gender as a repertoire of behaviours didn’t come from message boards, IRC channels or people I knew, but from an edited collection of linguistic articles. The first time I used gender neutral pronouns was in an essay analysing the linguistic interaction between my student radio co-presenter and me. These concepts blew my mind and started giving me words to describe myself and my experiences. Academia, perhaps weirdly, helped me find my way into activism.

I also believe that activism can enhance academic work. As I’ve alluded to previously, activism can help us ask questions – without the efforts of nonbinary activists like Nat, we wouldn’t have nearly as good an idea about how many nonbinary people there are in the UK and wouldn’t be so aware of the urgent need for more rigorous research in this area.

Some of the academic work I most respect has been from academics bringing their lived experiences and their own activism into their research. As an MA student, one of my formative books was Paul Baker’s Public Discourses of Gay Men. As corpus linguists, Paul and I examine large amounts of text to find patterns in them. These patterns don’t have to be grammatical, but can reflect cultural ideas – and to recognise that they’re present in the first place, let alone analyse them, you have to be familiar with the culture that produced the text. What so struck me about Paul’s work was the way he uses his experience as a gay man to research from within. He does not shed his identity as a gay man in order to pursue an impossible notion of objectivity – instead, it is his very subjectivity that makes it such an illuminating piece of work.

Finally, I believe that activism can help us become more compassionate academics – more open and aware of others’ experiences, more ready to accept others’ realities. Patricia O’Connor argues this when she says “Activist linguistics, as I see it, does not mean that the researcher skew her or his findings to support one group or one ideology or another. Nor does it mean that a famous linguist use her or his fame to support causes. Rather, an activist linguistics calls for researchers to remain connected to the communities in which they research, returning to those settings to apply the knowledge they have generated for the good of the community and to deepen the research through expansion or focus”

I wrote a chunk of my PhD in a university occupation. As an activist, I think I offer a much greater understanding of the frustration when peaceful direct action – petitions, meetings, lobbying – doesn’t get you anywhere. The women I studied for my PhD had campaigned peacefully for over 30 years before developing militant tactics! I got a better sense of the courage it took to take part in protests when it might lead to violence against you. I hope that this is reflected in my writing. It’s easy to judge people or campaigns for not making the same decisions as you would, but my activist experience highlighted what a difficult context suffrage campaigners worked in and the sometimes impossible decisions we have to make.

I’m still developing my new project on trans media representation, but I aim to be the kind of researcher Patricia talks about – connected to the community and using what I find for its good. I want my work to stand up to scrutiny from both activists and academic researchers. As I hope I’ve shown, I believe academia and activism can combine to create something better than their parts.

References:

Baker, P. (2005). Public Discourses of Gay Men. London: Routledge.

O’Connor, P. E. (2003). “Activist Sociolinguistics in a Critical Discourse Analysis Perspective”. In G. Weiss and R. Wodak (Eds) Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory and Interdisciplinarity. Basingstoke: Paulsgrave Macmillan

Titman, N. (2014, 16 December). “How many people in the United Kingdom are nonbinary?”. Retrieved from http://practicalandrogyny.com/2014/12/16/how-many-people-in-the-uk-are-nonbinary/