One of this things I’ve found interesting is the language that’s emerging. This post examines the language of the “we are the 99% tumblr. Meanwhile, Tiger Beatdown has some interesting analysis of who exactly is the 1% and an insightful, moving essay about the range of experiences of wealth, poverty and class found within the 99%.

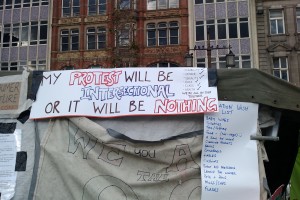

I’ve also been thinking about who an occupation excludes. I’d define an occupation as a radical reclamation of space where alternatives to mainstream society can be explored – things like communal living, consensus decision making, and sharing the work needed to sustain a community. However, the fact remains that we are products of this mainstream society and have internalised some of its toxic elements – sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, classism to name a handful. In a social justice context, not having to encounter these things are often described as ‘privileges’. There’s lots of material out there on privilege but I particularly like this primer on privilege and what we can do about it. It’s important to note that, while these can be manifested in individual interactions, they’re also embedded and reinforced by social institutions.

As a non-white, queer, female-assigned-at-birth person who has taken part in occupations, I’ve found that occupations tend to be full of very earnest people who are trying their very hardest not to reproduce structures of oppression but who often don’t quite manage it. As a non-white person, I don’t want to be told that someone – almost certainly white – doesn’t see race. As this essay describes, claiming that you don’t see race both makes my experiences of living as a non-white person invisible, and means that

that person also can ignore systemic nature of racism. That person can pretend that racial issues can be solved by making people act nicer to each other; however, focusing on eliminating prejudice and racism between individuals can obscure the need for eliminating the racism that is so deeply ingrained in our social institutions.

This is particularly important when engaging in the anti-cuts movement – how are you going to protest cuts to EMA disproportionately affecting women and ethnic minorities if you don’t see race and gender, or believe that racism and sexism can be addressed by everyone just being a bit nicer to each other?

An occupation that claims to be leaderless is not exempt from privilege: this essay, on how the Occupy movement’s non power structure perpetuates sexism, observes that

Even in movements that are formally leaderless, those with privilege tend to bring pre-existing power to the table, and that power can be dangerous. This is part of any communal space, no matter how well-intended; I can testify that, even in my own best efforts, and even with trusted friends, I’ve brought my own privilege to the table, created invisible hierarchies, and hurt people. Addressing how power works — who is seen to be powerful, who is exercising power, which kinds, and why, and how that looks like the old world and old structures of oppression we are trying to break away from — has to be a central part of any radical movement.

[…]

It’s hard to focus on what marginalized people are saying, when they’re reduced to a collection of photos for the purpose of telling us that they’re “hot.” The act of finding those voices, actively seeking them out, and listening to them, is harder than taking a photo. It’s also the work that can and must be done.

Failing to address sexism leads to sexual assault, and attempts to intimidate and silence those trying to address it, as seen in Occupy Glasgow.

So what can be done about it?

All Of Us Deserve To Feel Safe has published response cards as “a way of communicating to someone that they’ve made a space unsafe without having to deal with potentially intimidating confrontation. It includes a list of different ways that spaces can be made unsafe, with checkboxes for the relevant concerns.” They also have flyers with suggestions on how to make a space safer.

In addition to their very helpful suggestions, I’d like to comment that how labour is divided in the occupation is important. It’s not okay for men to be sitting around with mugs of tea while the women wash up, sort out the recycling, collect water and so on. I’ve seen this in an occupation before and it was shocking that these so-called radical men were content to allow this gendered division of labour to happen. This is some of the most visible stuff in an occupation – if you can’t manage to make this equal in your own space, how are you in a position to call for a fairer and more equal society?

I also think it’s important to not to treat any member of a minority group as a spokesperson. Sometimes, when I’ve wandered along to an occupation, I’ve immediately been pounced on and asked how they can make the occupation more friendly to ethnic minorities or women. I’m very glad that they’re thinking about this, but aside from the assumptions this makes about my gender identity, it also makes me feel like I’ve become a token minority – that I’m happy to have these conversations at their convenience, that I’m happy to have these sometimes difficult and exhausting conversations on demand. Sometimes I just want a brew and a chat, not to give an immediate workshop on anti-racism.

Finally, it’s crucial to listen. Creating an anti-oppressive space means that people belonging to less privileged groups will critique your efforts, and it’s essential that you listen to these criticisms and respond to them in a constructive manner rather than becoming defensive or aggressive. As the open letter to Occupy Glasgow shows, if someone criticises an occupation for allowing or enabling systematic oppression, she can be insulted, bullied and accused of trying to shut the occupation down from within. This is unacceptable behaviour – it silences the activists who did complain, it allows sexists a free pass, and it stops people making other criticisms. It can be difficult to hear criticism, but ultimately criticism coming from activists who are sympathetic to the movement comes from a place of caring and wanting the movement to be as inclusive as possible.

An occupation has to practice what it preaches. You cannot call for an end of one kind of oppression while perpetuating, however unconsciously, other kinds of oppressions and, however accidentally, silencing the voices of (other) minorities.