First in what seems to be an occasional series about interdisciplinarity. All posts can be found under the interdisciplinarity tag

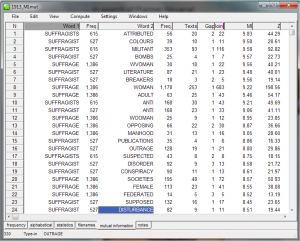

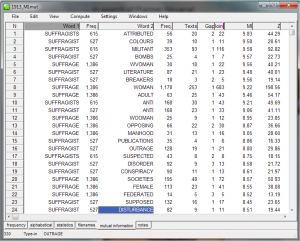

suffrag* and words statistically associated with it, calculated through Mutual Information (MI)

A couple of weeks ago I read

this article about treating humanities like a science and was a bit annoyed about it. In my experience, the big sweeping claims as illustrated in that article tend to be made by a) arts & humanities scholars who’ve suddenly discovered quantitative/computational methods and are terribly excited about it or b) science-y scholars who’ve suddenly discovered arts & humanities and are terribly excited about it. I’ve heard a fair number of papers where the response has been “yes, and how is this relevant?” because while it’s been extremely clever and done something dizzyingly complex with data, it’s either telling arts & humanities people stuff they already know or stuff that they’re not interested in. In my particular discipline people are very aware of the limits of quantitative work and we acknowledge the interpretive work done by the researcher. I do think quantitative methods have a place in arts and humanities, and in this post I’ll discuss some of the strengths of quantitative work.

Firstly, I should say something about my background and where I’m coming from. I’d describe myself as an empirical linguist – I look at language as it’s used rather than try to gain insights through intuition. My background is in corpus linguistics which basically means I use computer programs to look at patterns in large collections of texts. If this sounds suspiciously quantitative then yes…it is. Sometimes I look at which words are statistically likely to occur with other words, or statistically more likely to occur in one (type of) text than another, or trace the frequency of words across different time periods. My thesis chapters tend to have tables and graphs in them. I sometimes talk about p-values and significance.

However, these patterns must be interpreted. Computers can locate these patterns but to interpret them – to understand what they mean for language users – needs a human. As a discourse analyst, I’m interested in the effect different lexical choices have on the people who encounter them. I’m interested in power, in social relationships and in the ways in which identities and groups are constructed through language. A computer would find it difficult to analyse that.

So what can be gained from using corpus linguistics rather than purely qualitative approaches? Paul Baker outlines four ways in which corpus linguistics can be useful: reducing researcher bias, examining the incremental effect of discourse, exploring resistant and changing discourses, and triangulation

reducing researcher bias

Language can be surprising. We have expectations of how language is used that isn’t always borne out by the data. My MA dissertation looked at how male and female children were represented in stories written for children, focusing on how their bodies were used to express things about them. So, for example, I looked at his eyes and her eyes and what words were found around them. What I was expecting was that boys would be presented as active, tough and independent and girls would be presented as more emotional and gentler. What I found was that a) his eyes was much more frequent in the data than her eyes and b) that male characters expressed much more emotions than female characters. Part of this was because there was so much more opportunity to do so because of the higher frequency of his eyes, but the range of emotions – sorrow, joy, compassion – was really interesting and not what I was expecting from the research literature I’d read.

We also have cognitive biases about how we process information and what we notice in a text. We seek evidence that confirms our hypotheses and disregard evidence that doesn’t. We tend to notice things that are extraordinary, original and/or startling rather than things that are common or expected. If we select a number of texts for close, detailed analysis, we might be tempted to choose texts because they support our hypothesis. A corpus helps get around these problems by raising issues of representation and balance of its contents.

examining the incremental effect of discourse

Michael Stubbs, in one of my favourite linguistic metaphors, compares each example of language use to the day’s weather. On its own, whether it rains or shines on any particular day isn’t that significant. However, when we look at lots of days – at months, years, decades or centuries worth of data – we start finding patterns and trends. We stop talking about weather and instead start thinking in terms of climate.

Language is a bit like this. On its own, a particular word use or way of phrasing something may seem insignificant. However, language has a cumulative force. If a particular linguistic construction is used lots of times, it begins to “provide familiar and conventional representations of people and events, by filtering and crystallizing ideas, and by providing pre-fabricated means by which ideas can be easily conveyed and grasped” – through this repetition and reproduction, a discourse can become dominant and “particular definitions and classifications acquire, by repetition, an aura of common sense, and come to seem natural and comprehensive rather than partial and selective” (Stubbs 1996). A corpus can both reveal wider discourses and show unusual or infrequent discourses – both of which may not be identified if a limited number of texts are analysed.

exploring resistant and changing discourses

Discourses are not fixed; they can be challenged and changed. Again, corpora can help locate places where this is happening. A study using a corpus may reveal evidence of the frequency of a feature or provide more information of its pattern of use – for example, linking it to a particular genre, social group, age range, national or ethnic group, political stance or a small and restricted social network. A changing discourse can be examined by using a diachronic corpus or corpora containing texts from different time periods and comparing frequencies or contexts; for example, where a particular pattern is first found then where and how it spreads, if a word has changed semantically, has become more widespread, is used by different groups or has acquired a metaphorical usage.

triangulation

Finally, triangulation. Alan Bryman has a good introduction to this (.pdf) but it basically means using two or more approaches to investigate a research question, then seeing how closely your finds using each approach support each other. I tend to use methodological triangulation and use both quantitative and qualitative approaches. As well as supporting each other, using more than one method allows for greater flexibility in research. I like being able to get a sense of how widespread a pattern is across lots of texts but I also like being able to focus very closely on a handful of texts and analyse them in detail. It’s a bit like using the zoom lens on a camera – different things come into view or focus, but they’re part of the same landscape.

I find quantitative methods fascinating for the different perspective they offer. My background in corpus linguistics has also trained me to think about issues like data sampling, choosing texts to analyse and cherry-picking evidence. It’s taught me to think critically about what and how and why people search for in a text, and it’s made me methodologically rigorous. At the same time, dealing with so much data has made me very sensitive to language and how it’s used in different contexts. I think the author of that article might find some of the work in corpus stylistics fascinating – this is what my supervisor is working on, and having worked a bit with her corpus it’s easy to see how much qualitative literary analysis goes into it.

Returning to the article, I think this raises wider questions of how we approach interdisciplinarity, how we locate and approach research questions in fields not our own, and how we relate to colleagues in these other fields who are experts. If we are to engage in interdisciplinary research, then we are bound to be working in unfamiliar areas. We are going to encounter research methods and ways of thinking that are unfamiliar to us. The ways we approach things will have to be explained – why should a humanities scholar care about “a bunch of trends and statistics and frequencies”? How do we make these relevant to their interests and show them that these can both answer interesting questions and open up new avenues of research? Simultaneously, how do we gently make someone aware that they’ve just dipped a toe in our field and that there’s still much to learn?

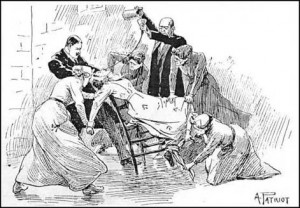

This is something that I’ve had to learn. I’m not a historian by background or training, but my area of research deals with historical issues. I’ve had to more or less teach myself early 20th century British history; I did this through extensive reading, gatecrashing undergraduate lectures and talking to historians. In a future blog post I’ll discuss this further so if you have any questions, let me know and I’ll do my best to answer.

References:

Baker, P. (2006). Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis. London: Continuum.

Stubbs, M. (1996). Text and Corpus Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell