Ah, the biannual Corpus Linguistics conference…the biggest date in the Corpus Linguistics calendar, the event that Tony McEnery described as more of a bacchanal than a conference.

This is one of my favourite academic conferences – it was the first one I went to as a wee MA student and I’ve been to every one since. Luckily it’s biannual or my wallet would be a thinner, sadder thing. I’ve done a lot of growing up at this series of conferences – first conference I attended, first conference I was a student helper for, first conference I got funding for, first conference I’m presenting at post-viva – and it feels a bit like home turf for me.

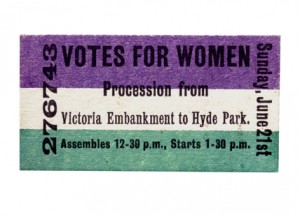

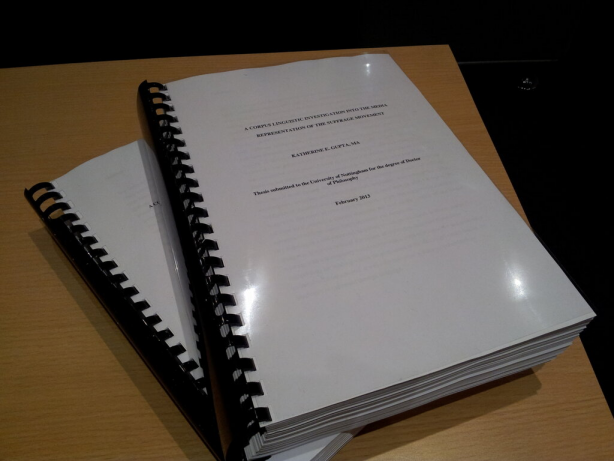

It was wonderful to catch up with friends and to meet new people. One of the conference helpers, Robbie Love, wrote a great post on his experiences at CL2013 and I’m delighted that he found it such a friendly place.I was presenting on my PhD research, this time trying to give an overview of how the three approaches I used in my thesis fit together: corpus linguistics, three approaches from critical discourse analysis and, underpinning all of this, an awareness of the social, political and cultural context in which the suffrage movement operated. I only had a limited amount of time to present so decided to show elements of the corpus linguistic analysis and some of the work I did on Emily Wilding Davison using Theo van Leeuwen’s taxonomy of social actors. However, I argued that without an awareness of the historical context, any analysis of these texts would be lacking.

I’ve uploaded the slides so have a look if you’re interested.

One of the cool things about big conferences is that you assemble your own experience. It reminds me a bit of big music festivals with headliners/plenaries most people make an effort to see, then dozens of interesting people and projects. That up-and-coming person you’ve been advised to see, that fascinating project you’ve seen an announcement about, that person that you’ll see because you know they’re a fantastic presenter, that thing you’ll go to because it sounds controversial and you suspect the response will be good, the friend you’ll go and watch for moral support, the person you used to work with back in the day and want to find out what they’re doing now, the one that you’ve never heard of but looks intriguing… Talking to someone else, I realised that it was almost as if we were at two different conferences! It was, once again, fascinating to see how many things corpus linguistics can be used to investigate.

Some of my highlights were:

Michael Hoey giving a characteristically energetic opening plenary

An intense discussion of p-values following Jonathan Culpeper and Jane Demmen‘s talk

Paul Baker‘s beautifully neat demonstration of triangulated methods

Claire Hardaker on trolling (she refused to give the site name of one place, referring to it only as the “internet hate machine” – naturally I knew exactly where she meant)

Alison Sealey on the People, Products, Pets, Pests project

An incredibly lively morning presentation from Laurence Anthony on AntConc

A whole team from Lancaster represented by Paul Rayson on the Metaphor in End of Life Care methodology

Sylvia Jaworska on representing the Other in tourism

Over the course of the conference we also drank a bar dry and drank 180 bottles of wine at the gala dinner, so good work everyone.

And, because Michael P-S claims it’s not a conference without me lurking on my laptop somewhere…