Just over a year ago, I got my first permanent academic job. It’s been a weird experience – a lower teaching load than I have previously had, but more administration and pastoral work. Perhaps the hardest thing to get used to is that I don’t have to move unless I want to. I’m not having to send off endless applications that will inevitably get rejected. I applied for conference funding and got it. These should not be unusual working conditions but they are. I carry something like survivors’ guilt with me: that I landed a permanent job while so many of my brilliant, talented peers didn’t.

Years of precarious employment have demonstrated how broken UK universities are: running on the goodwill of their staff who are themselves exhausted and running on fumes, engaged in a corporate project to turn students into consumers and staff as mere learning providers, and moving further and further away from a vision of the university as a public good, for knowledge and enquiry and exchange. Perhaps I am still a starry-eyed idealist but I want to work somewhere with a sense of justice and equality, that values the diversity of everyone in its community, and which rewards the labour of everyone – cleaners and professors, security guards and programme administrators, PhD students and librarians. The university would fail to function without any of us.

This post is necessarily focused on the experiences of one academic in the UK. The University and College Union (UCU) represents workers in UK universities and its work is focused on the UK, but many of the broad issues outlined here – inequality, precarity, high workloads and pay deflation – are seen in universities more globally.

UCU membership is limited to “academics, lecturers, trainers, instructors, researchers, managers, administrators, computer staff, librarians and postgraduates”. Other members of the university are represented by GMB and Unison but experience similar issues, especially in regards to insecure contracts and high workloads. I strike in solidarity for everyone employed by the university and who experiences these or similar conditions.

Finally, I strike for all those who want to strike but cannot due to their contract, visa or finances: I see you and I recognise your struggle.

Inequality

On average, women are paid 15% less than men are for the same work across the sector. This tool from UCU allows you to compare your salary to the average earned by the other binary gender and to other institutions.

Black and Arab academics at Russell group universities earn 26% less than their white colleagues. These inequalities are exacerbated by multiple axes of inequality: the same report shows that Asian women earn 22% less and Black women earn 39% less. There continues to be massive inequality at the level of professor. I would also argue that universities strategically recruit BAME academics internationally to hide the problems in UK BAME academic attainment. This is not to say that international staff don’t face unique problems: the threat of deportation and visa fees are just two of the ways in which the hostile environment is realised.

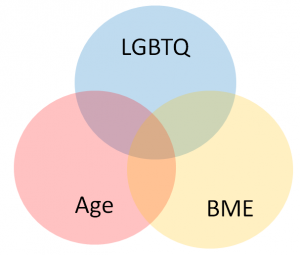

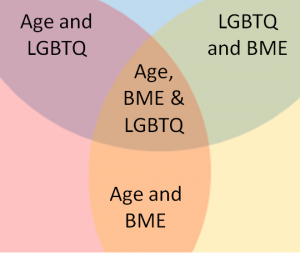

The existence of a national pay scale is meant to reduce these inequalities, but what happens in practice is that women, BAME and disabled people are appointed at the lowest rungs of the scale and face more barriers for promotion. One of these is realised in teaching evaluations: women and ethnic minority academics are more likely to be judged harshly in teaching evaluations which then becomes a barrier to promotion. Women in particular are expected to take on more administrative and pastoral duties, which either means doing less research, saying “no” and developing a reputation as someone who is “difficult”, or attempting to do it all and working far beyond your contracted hours. BAME or LGBTQ+ academics may find ourselves becoming a person that our BAME or LGBTQ+ students trust and someone they approach when trying to make sense of the unwritten rules and structures of academia. Again, this results in doing more pastoral care. It becomes incredibly difficult to juggle these things: as someone who is queer, trans and Asian, I feel responsible for my minority students and I want to help them navigate what can be an unfamiliar and even hostile place. However, there’s only so much of this I can do as an individual and a part of me knows that to get promoted, I would have to be ruthless about offering less in this area. I’m not going to because I think my LGBTQ+ and BAME students are amazing and deserve the best (and, in the absence of that, me), but it is something that I’m aware of.

Here is a link to material about racism in the British academy and here is a link to a comprehensive bibliography on gender and racial bias in teaching evaluations.

Precarious labour

There are more people chasing jobs than there are jobs in academia. Many academic jobs will have at least 100 applications, if not many more. In the UK, everyone who is invited to interview meets at least the essential and probably many of the desirable qualities listed in the job criteria: from my experience talking to other candidates, everyone will have a PhD in hand, some publications, appropriate – and in some cases, extensive – teaching experience and experience on a precarious contract, and it’s very much a case of who fits best with the department’s needs. Which is to say that universities rarely struggle to recruit academic staff, and people are desperate to get or keep a foot in academia.

There are two main types of precarious labour in academia: fixed-term contracts (often between 10 months to three years) and hourly-paid contracts. Being on one of these means that you are always, always worried about your future and whether you can stay in academia. It is constant, lurking stress: I started a 10 month contract and almost immediately started applying for jobs, It means that you can’t make long term plans: there’s no point settling somewhere because you will almost certainly have to move when your contract comes to an end. You don’t know what city you’ll be in – or even which country. I applied for jobs in Denmark and Scotland and Ireland and England – as a queer, trans person of colour, there were places where I simply wouldn’t be safe living and working. I had to limit myself to places where, ideally, there was legislation to protect me from discrimination and at the very least, I was less likely to get my gay brown ass attacked. I have moved city at a month’s notice, at one point sleeping on a friend’s air mattress because the contract on a flat had been delayed. Things like buying a house, having a child or even getting a pet is out of the question because you simply don’t know if you’ll have a job in six months time, let alone where it will be. It means that you don’t get to build a network of friends and a sense of community where you live because you don’t have time to establish yourself and will have to move again in a year anyway. It means that, if you have a partner and kids, you have to consider whether it’s fair to move your children and disrupt their friendships and education, and you have to decide whose career to prioritise: theirs or yours.

Hourly-paid contracts rarely recognise how much labour is involved. One job paid me £35 for each hour of teaching – but this didn’t include prep time, time dedicated for office hours, time spent answering student emails or marking. If I did the job properly to the best of my abilities, I would end up paying myself under minimum wage; if I didn’t, I would be letting down my students and jeopardise my future employment, there or elsewhere. I was lucky enough to work with some lovely colleagues who made every effort to shield me from taking on additional admin that I wouldn’t be paid for, and who made me feel that I was part of the department by inviting me to research events and to staff drinks or dinners. However, at my worst hourly paid lecturing job, I literally came in, taught for two hours, held office hours, then disappeared without seeing a single member of the department. I didn’t get any kind of induction and wouldn’t have known who to call in case of an emergency. No effort was made to even meet me on my first day or show me where I was teaching. I wasn’t part of that department – just a hired body to teach a module that no one else wanted to teach.

Hourly-paid contracts don’t allow any sort of research development funding; fixed term contracts may or may not allow this. Without institutional backing it’s difficult to develop research projects – you don’t have funding to attend conferences so you either don’t go or pay out of pocket, you don’t have the money to pay for access to research material, tools or software, you don’t have money to fund travel for research purposes and you don’t have consistent access to a library or electronic materials.

Hourly-paid contracts also don’t allow for sick leave or parental leave. If you get sick and are unable to work, you simply don’t get paid. I had surgery on a Wednesday in January 2017 (general anaesthetic, exciting painkillers etc) and was marking again the Saturday after (I wasn’t on the exciting painkillers by then because they made me…well, let’s just say that we didn’t get on). I was lecturing again barely two weeks afterwards, every jolt as the bus made its way up a bumpy road sending another shock through my stitched-together body. This isn’t something that I should have had to do, and it isn’t something that anyone should have to do. It’s not a sign of commitment or dedication; it’s a sign of exploitation.

Perhaps one of the saddest casualties of my years in the precarious wilderness was a relationship. My then-partner and I were both actively seeking academic employment. We couldn’t see a future where we could be in the same country, let alone both have academic or academic-related jobs reasonably close to each other. While there were other things that meant that the relationship couldn’t last, our stress about precarity, Brexit, internationalisation and visas was a major factor.

I was lucky enough to have the financial and emotional support of my parents, and indeed moved back in with them while I was on hourly contracts. I wouldn’t have been able to stay in academia long enough to have got a permanent job without their support, and even then we had some serious discussions about how long I could afford to keep doing this. There are so many who didn’t and don’t have familial financial support. The academic voices we are losing are the least privileged: disabled, female, BAME, working class, first generation to go to university, LGBTQ, with caring responsibilities (and any of these combinations). Academia will – already has – become a preserve of the privileged, and we lose diverse voices and perspectives and research and skills.

Did being precariously employed make me a better academic? Well, I got to see how other departments in other universities worked: I taught at five of them, including my PhD institution. I gained a lot of teaching experience: I taught 16 individual modules, and only one of them twice. I worked with a lot of people and learnt how to adapt to a new environment very quickly. However, it’s shaped my anxious tendencies: constructive criticism throws me into a spiral where I convince myself that I’m going to get fired any day, and I’m still not entirely sure how to build relationships with people who will hopefully be my colleagues for years. I’m not sure how to have input into something rather than adapt myself in the short term. I find it hard to think long-term at all: about what my research plans are for the next five years, let alone about what my career will look like for the next ten years, hell, even what the next year will look like.

This is what precarious labour is creating: a generation of academics shaped by uncertainty and anxiety. Some are simply not there, forced out by exploitative labour practices. Others are deeply entrenched in precarity and, without time or institutional support to develop their research, see little way out. Those of us who are permanently employed face a different set of challenges, not least that we may become complicit in it. Our hard-won research leave and parental leave is scope to create another precarious position.

Workloads

I am contracted for a 35 hour week. That means five days of seven hours a day. Admittedly my work schedule skews later (I’m a dedicated night owl) but the week before last I found myself pulling 12 hour days because there was no way that I could teach and attend compulsory meetings and hold office hours and get my marking done and respond to emails and meet my colleagues to discuss teaching, marking or students and respond to reviewer’s comments for a journal article and prepare teaching material for three modules, two of which I was teaching for the first time. I try to be very disciplined about not responding to emails outside working hours, but it’s hard to fit in that much work into a 35 hour week. It’s an even greater challenge for those employed on fractional contracts, for whom workload modelling never takes into account how long it actually takes to do any of these things. All of these issues are again exacerbated if there are any reasons at all that affect your ability to overwork: caring for children or other family members, disabilities, mental health issues, fatigue.

It happens at every level, from the teaching fellow who doesn’t have research built into their contract but who knows that their ability to get a permanent job depends on their publications to professors on whom work pressures are piled on. Compared to academia of yesteryear, we deal with much more admin, from the Research Excellence Framework (REF) to the Teaching Excellence Framework to the incoming Knowledge Exchange Framework (KEF). We are much more aware of student voices in the form of module evaluations and the National Student Survey (NSS), and the repercussions of a poor result. League tables are a constant source of stress

The second part of the UCU strike is taking Action Short Of a Strike (ASOS) which basically means working to contract. University senior management in some institutions have already threatened to dock pay if ASOS means you cannot fulfil your duties. They know that it is impossible to cram all of this into a 35 hour week, and indeed, universities are built upon the goodwill and free labour offered by their staff. We don’t want to leave a panicking student in the lurch so we respond to their evening or weekend emails, we don’t want to disappoint our co-authors so we work on revisions late at night, we can’t let marking deadlines slip so we scramble to get our marking completed within the 15 day turnaround period, we know that publications are how we get promoted so we squeeze that into an already strained workweek…

Part of the problem of academia is that the people who get into it tend to have a big streak of perfectionism and, I hope, an equally big streak of compassion. We don’t like failing our students, our colleagues, ourselves. We hold ourselves to high – even impossible – standards and get upset with ourselves when we don’t meet them. We suffer stress, poor mental health, burnout. And perhaps inevitably, the modern neoliberal university has seen this with bright, eager eyes and gone yes, yes we can exploit this.

Pay deflation

Academic pay in the UK has fallen at least 17% against the rate of inflation since 2009. What I get paid simply doesn’t go as far as it did a decade ago. According to this UCU tool, I would be earning an extra £8000 a year if salaries had risen in line with inflation since 2010. As someone living in London, it’s also important to note that London weighting hasn’t kept pace with the fast rise in living expenses in London. Significantly more than 35% of my salary goes on rent. This hits harder because after a PhD and precarious labour, many early career academics don’t have much in the way of savings. Assuming I don’t become redundant or otherwise unemployed, I basically have about 35 years of a proper salary before I retire (assuming I retire at 70, ahahahaha excuse me while I lie down and weep). I have to earn a lot in those 35 years to make up for the 15 or so years when I was not earning enough to save because I was studying for my BA, MA and PhD and then in the precarious wilderness.

Despite all this, I want to believe that universities can do better, can be better. I want contracts that will allow staff to flourish. I want an end to pay gaps and precarious employment. I don’t want anyone to be employed on an hourly contract unless it’s something that they actively want because teaching is a side gig that they fit around a substantially paid job. I want space for wonder and curiosity and imagination. I want to not spend my weekend working or prone on the sofa. How about it?