This is a difficult post to write.

On 31st July 2022, I took voluntary severence from the University of Roehampton.

The two programmes I was involved in, the BA English Language and Linguistics and the BA English Language and Literature, are being taught out. In a few years, they will cease to exist.

Even now, I feel the grief rise in my throat as I type.

There was so much about Roehampton that I adored. The scale of the four historic colleges meant that you knew people on the other programmes based there, the head of college, the college student welfare officer (SWO), the programme administrators, the receptionists, the catering staff. It felt very human and very humane.

The campus, at once small and homely and expansive and green, meant that you couldn’t cross it without running into someone you knew. It was a particularly friendly campus with people who were eager to reach out and seek a connection. In these connections I found all sorts of things: a fresh academic idea, a point of connection between disciplines, an interesting bit of campus gossip, a useful resource to direct students towards, someone willing to help you with a project, someone you could help in return, or just the useful information that the Hive were serving up something particularly delicious so get there quick. My goodbye email included people from all five Schools, the library team, the welfare team, the chaplaincy and even a couple of people from senior management. As I typed in their names, I was genuinely astonished at how many people I’d managed to meet over the course of two normal and two pandemic years.

The quiet commitment to providing for students’ wellbeing was holistic, from weekly community lunches to wellbeing/counselling/mental health support to Growhampton, a student-run project caring for (often ex-battery farm) chickens, growing an edible campus and using the eggs and harvest in an on-campus cafe. The wellbeing system was the best I’ve ever encountered in a university setting – you knew who the college SWO was, you’d gone for tea and cake with them, and so you knew exactly who you were directing your students to and how they would be listened to and supported. I could pop an email to the SWO and I wasn’t emailing an anonymous group account – I was emailing Jo, who I’d seen that morning or Em, who I’d had a cup of tea with last week. I could reassure my students that I knew Jo or Em and that they were lovely. It made the process of asking for help that much more approachable.

My colleagues, who were both brilliant and supportive. So many people were doing so many interesting things – I wanted to sit down with pretty much everyone and pick their brains. From them, I learnt how to balance research and teaching, how to run a disciplinary meeting, how to chair a programme board, how to convene a programme. I learnt how to be gracious and generous as both a colleague and a teacher. I knew that they had my back and would step in if I ever needed help, just as I would do so for them. I had the joy of team-teaching on a Digital Media module and it was some of the most fun, playful and adventurous teaching I’ve ever participated in. I am so sad that so many of them have also lost their jobs, and sad for those who remain to teach out the programmes that we so carefully developed and nurtured.

Most of all, I am deeply deeply sad for our students. The statistics will tell you that many of our students were working class, first generation, Black or minority ethnic, disabled, student parents, student carers, care leavers, mature students or, in many cases, a combination of these. They won’t tell you that our students were spirited, determined, occasionally frustrating, and nearly all had an interesting, unique journey to university. One was a mature student who had been raised in a strict religious community; after she left, she took a chance and applied to university and, to her great surprise, was admitted onto the Foundation programme. One had her confidence destroyed during her A-levels; she asked if she could talk to me after our first year induction session and wept in my office, believing that she wasn’t meant for university. One told me with grim pride that she came from the worst school in the borough, and was determined to become a teacher so that she could help others flourish. All three of these students have graduated with Firsts and 2.is, producing work that I would have been delighted by at any of the many other universities at which I’ve taught. Many have struggled with their physical and mental health, and I’ve fought for these students to get the support and flexibility that would allow them to fulfil their potential.

So many of these students would have floundered in big Russell Group universities or just silently disengaged. Our small cohorts meant that we got to know them and they got to know us. I like to think that they talked to me not just as their academic guidance tutor or programme convenor, but as as an individual that they’d come to know and trust. Roehampton was the first place where I’d properly got to develop my own modules over a period of years (rather than the one-and-done of so much of my previous teaching) and the nature of teaching modules on identity and gender meant that I was very careful to create spaces that were respectful, open and supportive. I brought (some of) myself into my modules, and my students brought (some of) themselves. They shared in beautiful, unexpected ways: the student parents who discussed how they were raising their children; the young women who articulated shifting between the different worlds of university, work, religious life and family life; the young men who were thinking carefully about masculinity and consciously choosing to be kind. At least one student came out to me every time I taught the module on the Sociolinguistics of Gender – not necessarily because they’d come to that realisation, but because they decided that I was someone they could trust with that knowledge.

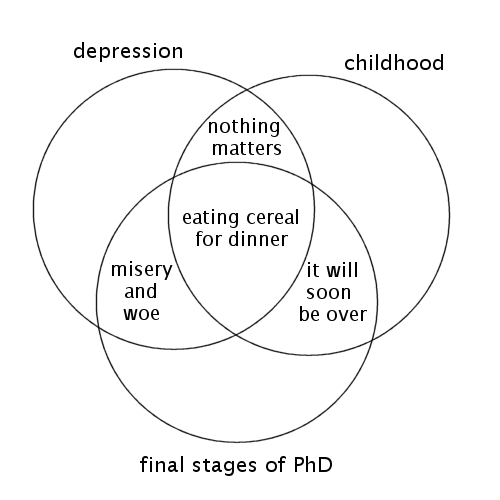

I’m selectively writing about my experiences at Roehampton. There are things that I cannot write about under the terms of my settlement agreement. Do not believe for a second that everything was perfect: it wasn’t. It is always stressful being at a small post-92 in an expensive city that doesn’t have large financial reserves, compounded by the pandemic and the lifting of the student cap. I had more than my fill of stressful days and sleepless nights.

I am choosing what I will remember.

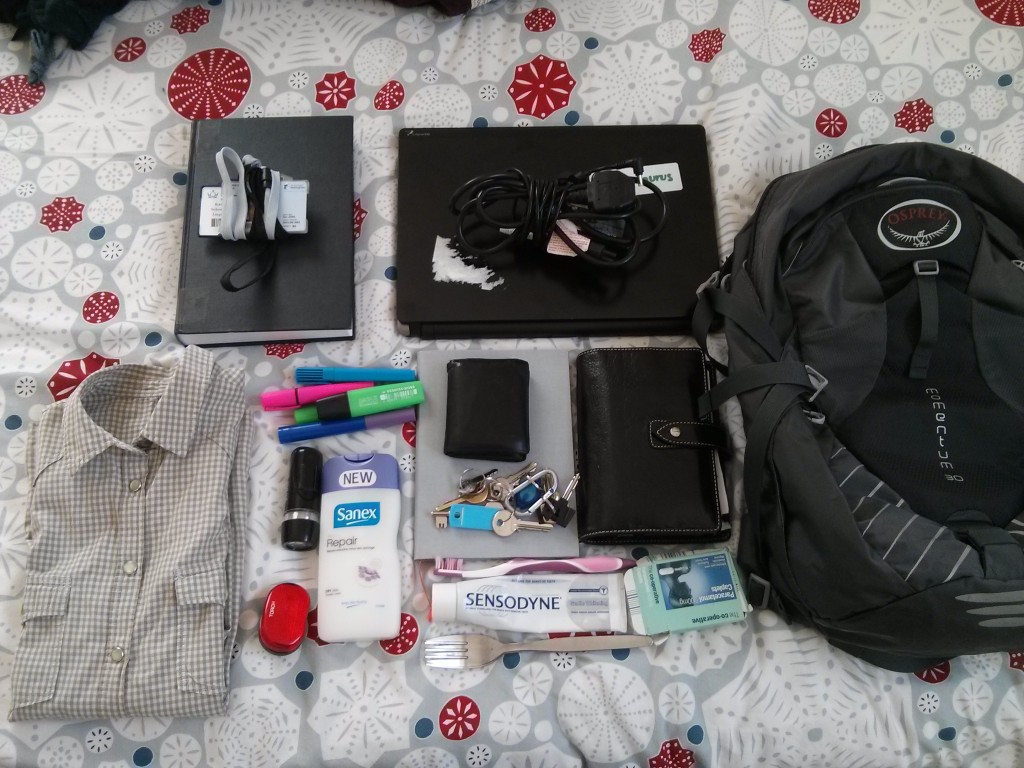

I am choosing what I will take with me.

What I have learnt is that people and the connections you make are important. Without that, there is nothing. The institution will never love you back, and it will never reward (or even acknowledge) loyalty or sacrifice. There is no point in offering loyalty to an entity incapable of valuing it.

People, though – people are the lifeblood of any organisation. I choose to take from these nearly four years at Roehampton the following: a deep sense of care for my students and colleagues; the aim of creating spaces that are expansive and welcoming and supportive and challenging; the joy of helping someone flourish and the fierce pride in their achievements (whatever they may be); the vocation of teaching students who are underrepresented in higher education and ensuring that they have the resources and support they need to be successful; the recognition of people as whole beings and not solely work colleagues or students. I hope I will always value people and connection, and place them at the centre of my pedagogy.

At the moment, It is still too raw, too painful. But one day I hope I will be grateful for these years that have shaped me into a kinder, more thoughtful, more generous, more gracious person and scholar.