This is a post about trigger or content warnings. The specific content I will be discussing is sexual assault, but there will be brief mentions of police violence, forced feeding, transphobia and death (cancer and suicide). I am lucky in that I don’t experience PTSD; I’m therefore writing with that perspective (and privilege). However, there have been times in my life when I’ve benefited from content warnings and there are still things I treat with caution. I prefer the phrase “content warning” because triggers vary so widely and encompass so many things – as well as words, they can include objects, scents and music and people with similar experiences may have different triggers. “Content warning” avoids some of those issues.

This post is prompted by an event, Transpose: Tate Edition. Transpose is a semi-regular LGBTQ event organised by CN Lester showcasing writers, artists, musicians, photographers and performers from within the LGBTQ – but especially the trans – community. Because it gives lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer artists and performers a space, Transpose often explores difficult things: our bodies, our families and relationships, the violence meted out to gender non-conforming bodies. I should mention here that I’ve performed at the London Pride and Halloween Editions

You can read DIVA’s review of Sunday’s performance, All About Trans’ review of the evening, an extract of CN’s longer meditation on gender, bodily experience and art and Fox’s notes on his performance.

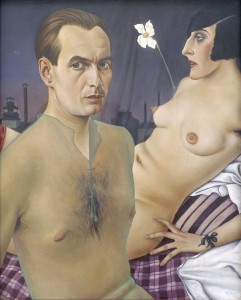

Self-Portrait 1927 by Christian Schad. Image from Tate Modern

At the end Jacques described the destruction of Hirschfeld’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft: its libraries were burned and the women and staff attached to it had disappeared – either in hiding, trying to escape the country or dead. The bohemians of Berlin were scattered. Heike was never heard of after the attack on the Institut on 6 May 1933. Jacques paused, allowing us to think about that. Then she announced that Heike’s story – Heike’s life – had been a work of fiction.

It was an astonishing double-punch. As a writer and an academic I was incredibly impressed with Jacques’ work and how she wove the real and the fictional together. A huge amount of careful, detailed research had gone into the creation of this piece encompassing history, politics and art history. It explored bodies as they’re perceived by their owner and by others, the rare opportunity for us to see ourselves as others see us, the different subjectivities and untruths and exaggerations offered by words and paint, the hurt of discovering that someone sees you very differently to the way you try to make yourself be seen. As a writer I recognised that Jacques’ skill in telling an undeniably powerful story. I would very much like to read it again.

But as a friend I knew some people in the audience had traumatic experiences of sexual assault. As an activist I think about the spaces I am in and which I help create, and how they embody and facilitate ways of being and interacting. One of the things that is vitally important to me is consent, and I see content warnings as being part of that.

Like Mary Hamilton, who discusses the problems of trigger warnings spreading from closed to public communities, much of my early experience of content warnings was in closed livejournal communities. As Hamilton notes, “[t]rigger warnings on the web were born in communities trying to balance the need to speak with the need not to hear”. Through various textual conventions like ROT-13, clever use of CSS and cut tags that hide a portion of text and have to be clicked on to view the hidden text, there were means to balance the complex needs of different users. The default behaviour was to hide potentially distressing material. Viewing such material had to be a decision, and members of that community were given a choice in whether they unscrambled the text, whether they highlighted the CSS formatted text, whether they clicked to view the full entry.

However, Hamilton is responding to other pieces discussing content warnings in more public arenas. Crucially, these arenas encompass not only online written and visual communication, but spoken and offline print communication. The New Republic’s “Trigger Happy The “trigger warning” has spread from blogs to college classes. Can it be stopped?” and the Guardian’s “We’ve gone too far with ‘trigger warnings'” argue against content warnings for similar reasons. A valuable alternative perspective is offered by this post by Tressie McMillan Cottom; see footnote [1].

The New Republic and Guardian articles both argue that content warnings

[…] are presented as a gesture of empathy, but the irony is they lead only to more solipsism, an over-preoccupation with one’s own feelings—much to the detriment of society as a whole. Structuring public life around the most fragile personal sensitivities will only restrict all of our horizons. Engaging with ideas involves risk, and slapping warnings on them only undermines the principle of intellectual exploration. We cannot anticipate every potential trigger—the world, like the Internet, is too large and unwieldy. But even if we could, why would we want to? Bending the world to accommodate our personal frailties does not help us overcome them.

These articles, to me, miss the point on several levels.

Firstly, they overcomplicate content warnings to the point of creating a straw man. Content warnings have been around a long time – consider the ratings (and justification for them) on films or the phrase “this report contains scenes some viewers may find upsetting” on the news. When thinking about content warnings, I realised that my teacher had given the class a content warning in secondary school. I was 14, and we were just starting our GCSE studies. The English Literature course focused heavily on war poetry. Before we started reading, analysing and discussing the poems, our teacher told us about the content of the material we were about to deeply engage with and asked us what our experiences of war had been: had we been involved in any way? had our families? did we have relatives who had been the armed forces, or were currently in them? We had the opportunity to discuss these things and flag these up for our teacher so she knew something about us, our experiences and what we were bringing to these poems.

Contrast this with another experience: I was 19, and in my first year of my English degree. It was a close reading tutorial; we’d get an unseen poem, spend an hour discussing it then write a formative essay on it. The poem we were analysing that hour was a response to Tennyson’s “Crossing The Bar” I don’t remember much about the poem; it was about someone being told of someone’s death, and struggling to come up with a eulogy before the clear, tolling words of “Sunset and evening star, / And one clear call for me!” came to him. I sat, silent and miserable, and the tutor rebuked me for not being my usual responsive self. My friend – also 19, a schoolfriend – had died of cancer the previous day; I’d been told the previous evening. To frame it in terms of the educational institution as the New Republic and Guardian articles want to do: was this good pedagogy? I could have brought a unique perspective to my analysis – the rawness of grief, the awareness of one’s teenaged mortality. Instead I sat there silent, barely able to engage with the poem.

Secondly, they argue that anyone needing a content warning is a special, selfish snowflake demanding the world be shaped to accommodate them. I suspect that of all people, those who have experienced trauma know that the world is not shaped to accommodate them. There’s a more interesting issue of how educational institutions should teach and engage with deeply problematic texts, and the duty of care we have towards our students and how this should be manifested, but I think that’s an issue for another post.

Thirdly, they conflate empathy with consent. Content warnings enable someone to make an informed decision about whether they want to participate in an event and if so, how best to prepare themselves. Sometimes this may mean saving reading material for another day when your mental health is less fragile. Sometimes it means engaging with material in a different context – reading a book in a busy cafe rather than alone and in the quiet of your bedroom in the dark hours. Sometimes it means scheduling activities differently to make sure you don’t get trapped in your own head – for me, this might mean spending the afternoon reading concordance lines about distressing things and seeing friends in the evening. If I know in advance, I can make a choice about how I structure my time. By not giving a content warning, you remove that choice.

I am reminded here of China Miéville’s[2] concept of choice-theft in Perdido Street Station. In it, sexual assault and rape are conceptualised as “choice-theft in the second degree” (with murder being that as the first degree). As a character explains,

“To take the choice of another… to forget their concrete reality, to abstract them, to forget you are a node in a matrix, that actions have consequences. We must not take the choice of another being. What is community but a means to..for all we individuals to have…our choices.

[…]

But all choice-thefts steal from the future as well as the present”.

[…]

What he saw most clearly, immediately, were all the vistas, the avenue of choice that [Spoiler] had stolen. Fleetingly, [Spoiler] glimpsed the denied possibilities.

The choice not to have sex, not to be hurt. The choice not to risk pregnancy. And then…what if she had become pregnant? The choice not to abort? The choice not to have a child?

The choice to look at [Spoiler] with respect?

I sometimes research really horrible stuff – they include police assault, forcible feeding and violent transphobia. I’ve spent a considerable amount of time going through thousands of concordance lines of transphobia, suicide and misgendering. Yes, reading it was upsetting and reminded me of the street abuse I’ve received, the risks I take by existing. But I believe, passionately, that it is vital to talk about these things – to haul them out and shine a ruthless light on them. I believe it’s important to understand how these things happen, to dissect them and understand their anatomy. How else can we challenge them? But when I talk about these things – when I present on them, when they emerge in my creative work – I give content warnings. My decision on when and where and how I engage with these things are not anyone else’s; I do not have the right to force someone along with me.

Instead, I seek my audience’s consent to come with me. I ask that they trust me enough to put themselves in my hands, that I will lead them through my academic or creative work without inflicting further hurts. I ask for their trust that I will talk about difficult things, but to do so in a way that offers them something: a vocabulary, a reconceptualisation, a challenge. I make it clear that they can leave the room and I won’t be offended or upset.

I refuse to enact further violations of consent.

I ask for their trust.

I offer them a choice.

__________________________________

[1] Tressie McMillan Cottom argues that “no one is arguing for trigger warnings in the routine spaces where symbolic and structural violence are acted on students at the margins. No one, to my knowledge, is affixing trigger warnings to department meetings that WASP-y normative expectations may require you to code switch yourself into oblivion to participate as a full member of the group. Instead, trigger warnings are being encouraged for sites of resistance, not mechanisms of oppression”. I’ve tried to reflect this tension between content warnings and sites of resistance in my argument. ↩

[2] I’m unhappy about referencing Miéville for reasons outlined in this post [CW: non-explicit discussion of emotional abuse]. I’ve chosen to acknowledge this and to also warn for the content in a way consistent with the argument I make in this post. If any writers have explored a similar concept, I’d be very interested in reading their work. ↩

Great piece. I was at that Transpose and found Jacques’ talk difficult – I didn’t leave but I was uncomfortable and tense, and I suspect I would have been ok if I hadn’t been blindsided by what you call the double-punch effect: the brutality of the content was bad, and the reveal that it was fiction was worse. It was like Jacques had chosen to shock and upset not once, but twice, and in a deliberately callous way. I don’t know, I feel like I’m being harsh – it’s hard to pin down what exactly was wrong with her choice to frame her words in that way – but I can’t pretend I didn’t have a really strong reaction to it.

These words of yours seem particularly relevant: “Secondly, they argue that anyone needing a content warning is a special, selfish snowflake demanding the world be shaped to accommodate them. I suspect that of all people, those who have experienced trauma know that the world is not shaped to accommodate them.” I totally agree, and would add this: requesting content warnings is a way of trying to shape oneself to the world. If someone is triggered by content and has to leave / close the window / quit the class / block their ears, then they have been forced to remove themselves from the vicinity of the trigger. By requesting a warning, it seems to me that those people are trying to ensure they *can* participate in ‘normal’ things, just as “normal” people do. Seems like the opposite of selfish to me.

The full piece on China Mieville’s abuse of women is here (trigger warning) and frighteningly comes with a new headline saying that ‘identifying details have been changed following a terrifying legal threat.’ http://bidisha-online.blogspot.co.uk/2012/12/emotional-violence-and-social-power.html

In the piece there are other links to articles by the same author, including to a brilliant piece about triggering itself. (Trigger warning!)

Solidarity.

Pingback: Learning and teaching consent with a parrot – mixosaurus

Pingback: Talking about desire, talking about fucking – mixosaurus