I’m delighted to confirm that I will be speaking on the Hidden Histories panel as part of the East London Suffragette Festival.

The event runs between 10am – 5pm on Saturday 9th August; the panel starts at 11:45am. It’s free and is at Toynbee Hall, London – a place seeped in the radical history of the East End and where many notable suffrage campaigners spoke.

The Hidden Histories panel will be discussing who gets left out of the history books, how history is shaped by what is recorded and who records it, how a multiplicity of narratives are boiled down into stereotypes, and why it is important to uncover these hidden histories.

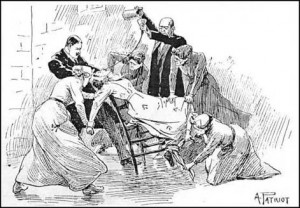

I’m really excited about speaking because this ties in incredibly well with my research on newspaper discourses of the suffrage movement; it was striking how differently The Times was talking about the suffrage movement to how campaigners themselves saw both the campaign and themselves. I argue that the multiplicity of suffrage identities, aims and experiences were conflated into narratives about suffrage disturbance, outrage, violence and disorder. This extended to blurring the distinction between constitutionalist and militant approaches – a distinction that suffrage campaigners saw as very important and which they frequently wrote and spoke about.

However, there is one place in the newspaper where suffrage campaigners’ voices are heard: in the letters to the editor. In my forthcoming book, I analyse this section of the newspaper separately – and find that the areas of concern are very different. Discussion of suffrage direct action framed in terms of disorder and violence appear much less frequently – instead, there is concern for prisoners, discussion of leadership and clever, witty refutations of stereotypes of suffrage campaigners.

I believe that the media representation of the suffrage movement is not so different to the media representation of other protest movements. Having been involved with various social justice, feminist, race and queer activism(s) for over a decade, I am aware of the ways that even peaceful direct action can be reported as disturbingly, frighteningly violent. Like the suffrage campaigners, we have debates about the forms our protests should take, how to create understanding and sympathy from those who don’t know much about us, how to include people in our movement, how to protect ourselves from violence, intimidation and burnout, how to create and maintain sustainable, compassionate activism.

Uncovering these so-called hidden histories (hidden to whom?) helps us challenge dominant narratives, locate diversity in campaigns and, ultimately, recognise historical campaigners as people not so very different from ourselves. In researching the suffrage movement, I also discovered a history – and a legacy – of activism.