[content notes: discussion of sex and relationships including consensual kink and non-monogamy. Some discussion of homophobia and transphobia. Non-detailed discussion of sex acts]

I was surprised to find myself so annoyed by Pride in London’s 2017 slogan, “Love Happens Here”. I admit that I am an unromantic grouch, but surely this slogan was harmless? The way in which people engaged with this at a museum LGBT Late during Pride month was rather charming – a map of London with rainbow sticky notes on which they’d written memories of their first kiss, where they met their partner and so on. It was a lovely piece of queer remembering and storytelling. But something troubled, and continues to trouble, me about it.

I was surprised to find myself so annoyed by Pride in London’s 2017 slogan, “Love Happens Here”. I admit that I am an unromantic grouch, but surely this slogan was harmless? The way in which people engaged with this at a museum LGBT Late during Pride month was rather charming – a map of London with rainbow sticky notes on which they’d written memories of their first kiss, where they met their partner and so on. It was a lovely piece of queer remembering and storytelling. But something troubled, and continues to trouble, me about it.

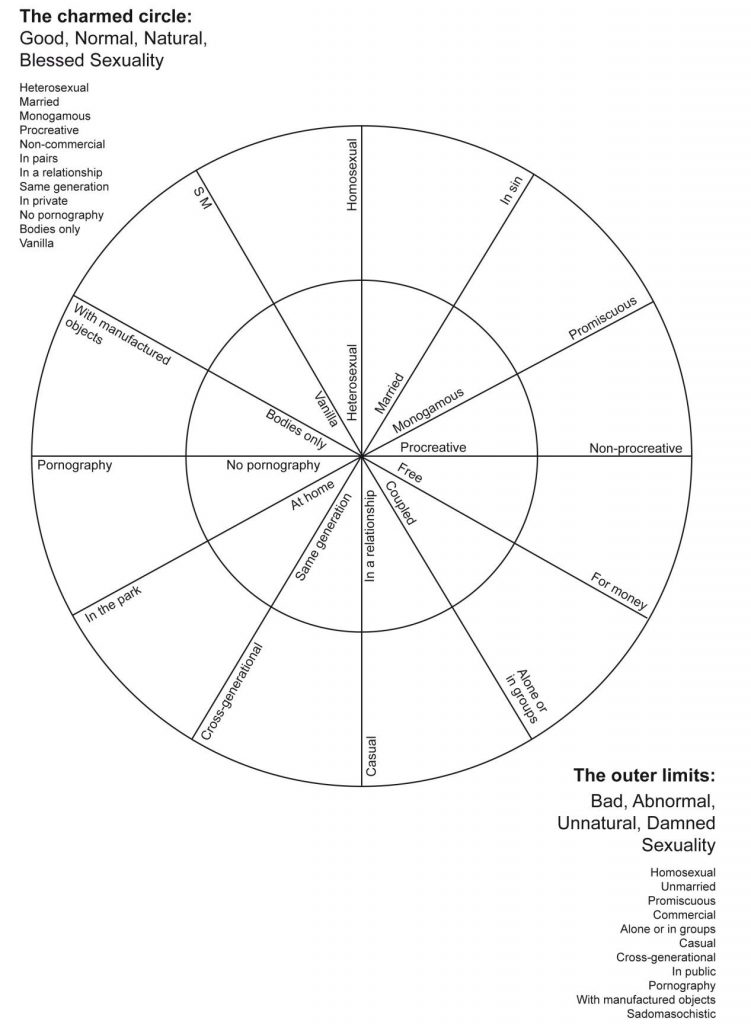

My problem lies with the word “love”. I’ve recently been thinking about Gayle Rubin’s discussion of social values afforded to different kinds of sexual relationships. She identifies types of relationships that are typically viewed as good/natural/desirable, and other kinds of relationships that are typically viewed as bad/unnatural/undesirable. It is important to note that these labels reflect social values and views rather than Rubin herself labelling them as good or bad.

These dynamics are binaries: so for example, relationships can be monogamous (good/natural/desirable) or non-monogamous (bad/unnatural/undesirable), or they can involve human bodies only (good/natural/desirable) or involve manufactured objects (bad/unnatural/undesirable). Rubin described the good/natural/desirable components as within a Charmed Circle, and the bad/unnatural/undesirable components as beyond the limits of socially acceptable sex. So we have

| Charmed circle | Outer limits |

|---|---|

| heterosexual | homosexual |

| married | unmarried |

| monogamous | non-monogamous |

| procreative | non-procreative |

| non-monetised | monetised |

| in pairs | alone or in groups |

| in a relationship | casual |

| same-generation | cross-generational |

| in private | in public |

| no pornography | with pornography |

| with bodies only | with manufactured objects |

| vanilla | BDSM |

Homosexual sex, therefore, is out of this charmed circle simply by virtue of being homosexual. However, there are other things that we might associate with sexual practices among LGBTQ people: the use of manufactured objects in the form of sex toys; non-monogamy in the form of polyamory, open relationships and other forms of ethical non-monogamy; sex in public through cruising and cottaging; casual sex; non-vanilla sex (which also may include manufactured objects); sex and relationships between people with an age gap.

At the same time, these things are not static. Over time, some practices and types of relationships may become more socially acceptable. Rubin argues that there is an area of contest, a grey area of potentially acceptable kinds of “bad” sex: unmarried heterosexual couples, promiscuous heterosexuals, masturbation, and long-term, stable lesbian and gay male couples (note that this excludes bisexual, trans and queer people). Therefore, homosexuality might be acceptable in some cases – if, in other words, it ticks the boxes for the rest of the charmed circle.

In order to be acceptable to wider, heterosexual society, LG(btq) people must become very, very good at mirroring relationships within this established charmed circle. The charmed circle focuses on stability and love. How should non-heterosexual couples make their relationships demonstrate stability and love? Same sex marriage equality, the ability of same sex couples to adopt and issues of reproductive technology have been areas of public debate, fulfilling the charmed circle needs of “marriage” and “procreation”. There are tensions about assimilation, heteronormativity and homonormativity – issues of how much LGBTQ people should want the same things as heterosexual people, how similar LGBTQ lives should look to heterosexual lives, and what becomes “normal” (and what is excluded from this new normality).

Heterosexual people are increasingly happier about accepting LGBTQ relationships as long as our love is visible and intelligible to them. As long as they can see that our relationships are centred around love (and it is a love which they can identify and understand), they don’t have to think about sex.

I’m uncomfortable with this emphasis on LG(btq) love.

Firstly, homosexuality was only decriminalised 50 years ago. Section 28 effectively banned any teaching of LGBTQ issues in schools for fear it would be perceived as promoting homosexuality; it was only repealed in 2003. So many of us grew up scared and alone – scared of arrest, scared that we were going to catch AIDS because we were told that’s what happened to people like us, scared because we didn’t feel the things we were meant to feel and there was a huge, cavernous silence around what we could be. Section 28 is no more but the Stonewall Schools Report shows that LGBT children continue to be bullied in schools, and that trans students are particularly targeted. LGBTQ people from ethnic minorities and religious communities can face huge pressure to act straight, including being forced into heterosexual marriages.

For too many of us, love is a luxury – instead, our relationships are furtive and fleeting, on hook-up apps or with an expiry date of hours, not recognised by our families or communities, dangerous for us to be in. We are not allowed to love, to luxuriate in settled, loving, married partnership. To be told that your desires are unacceptable but might be tolerated only in the context of a long-term, loving partnership that you are not remotely equipped to build is a cruel catch-22.

Secondly, being on the outer limits of acceptability means that LGBTQ people have had contact with other groups at the limits (or, indeed, are part of these other groups) and have had the freedom to reimagine relationships. Not all LGBTQ people are going to be engaging in non-monogamy, sex work, kink, casual sex, public sex or cross-generational relationships, but I think it’s important that we do acknowledge the hard-won wisdom of people who have experienced these kinds of sex and relationships. We may have learnt to talk about communication and to critique the relationship escalator from poly and non-monogamy practitioners, learnt about consent (and being safe and risk aware) and the importance of communicating our desires and our limits from people into BDSM and kink, experienced non-nuclear families of choice, known or experienced child-rearing through being a single parent by choice, part of a poly group, or as donors of gametes, learnt about boundaries and self-care from sex workers, learnt about sexual health from people who practice casual sex. We may have been able to pass on our knowledge and teach other people.

We may be able to use this awareness to reimagine a binary of good and bad relationships that, as M-J Barker does here, places sex and relationships which are not consensual, not informed, and which insist on strict, non-negotiable gendered roles within sex at the outer limits. They place consent, fluidity, diversity and being critically informed within the charmed circle – something that I think is valuable for all sex and relationships, no matter how long-term, monogamous, vanilla or romantic they are.

We may value love – but also be able to recognise that it doesn’t describe all the queer experiences (histories, relationships, desires) out there.

So here’s to munches and dungeons. Here’s to cottaging and cruising. Here’s to fumbles in gay club toilets and fucking by the bins in the alley. Here’s to kissing on the bus. Here’s to caring, tender casual sex. Here’s to safewords and using them. Here’s to that look, the look that says “I’m sorry about my homophobic relatives” and “I’m sorry they’re calling you my friend instead of my girlfriend” and “let’s get out of this place”. Here’s to Grindr and when it crashes due to the sheer density of gay people in a room. Here’s to whipmarks that say “I love you”. Here’s to love without sex that is every bit as important and life-changing and life-shaping. Here’s to fuck buddies and hookups. Here’s to sex without love because you’re all into it and everyone knows that this is casual and meant to be fun.

Here’s to love that doesn’t have to be visible.

Here’s to love that is expressed strangely and queerly.

Here’s to kindness and communication and consent and community, without which love couldn’t exist.

Here’s to decentring love.