Second in what seems to be an occasional series about interdisciplinarity. All posts can be found under the interdisciplinarity tag

One of the most daunting things about my thesis was that I essentially had to learn a new discipline. I could have treated my corpus of hundred year old newspaper articles like a contemporary corpus – the corpora I’d used until then (the British National Corpus, the Guardian corpus and two corpora I’d assembled myself, one of music reviews and the other of children’s stories) were of my time and cultural context and, while I obviously researched the area, I didn’t have to learn about a different time period.

However, I knew that if I was to do any kind of (critical) discourse analysis with these historical newspaper texts, I had to learn about the historical context they operated in. If I didn’t, I would be incapable of recognising discourses – they simply would not register as significant to my contemporary eyes. I would not understand their significance, or the impact they had. The nuances would be lost on me and my thesis would make for possibly an interesting corpus analysis, but useless for anyone interested in the historical or social aspects.

The trouble was that I hadn’t done any history since GCSE. At that age I was pretty sure that my interests lay in warfare, sickness, medicine, death and social history, and not in kings, queens and the nobility. The prospect of being taught by my history teacher for another two years was not a prospect I was willing to entertain. Despite loving history, I reluctantly chose not to study it at A level. As such, I had a lot to learn.

Be aware of the field(s)

My first task was simply to understand the historiography – who was writing about the suffrage movement and how they positioned themselves within the field. I tried to understand the debates within the field, and how people’s research responded to others’ research. I learnt something of the waves of research about the suffrage movement – the first waves comprising of personal memoirs and scholarship focusing on the WSPU, London-based organisations and leading figures of the movement, and a second wave starting in the 1970s and focusing more on hitherto marginalised figures, experiences, ideologies and organisations. There were also historians seeking to synthesise these various perspectives.

I also sought to understand the wider context of the time period – what was going on in terms of politics, family life, Empire, work, health? What were the assumptions about gender roles and how women were supposed to behave? These were the things that were going to come up in the newspapers and which I had to be acquainted with.

One of the ways I did this was to read – a lot. The other was to go along to undergraduate history lectures. These were useful in supplying context and when it came to the lecture on the suffrage movement, I was delighted that it was all stuff I was newly familiar with. This suggested that I was on the right track.

I am also immensely grateful to Dr Chris Godden and Dr Lesley Hall who were generous with their time and advice and who didn’t laugh at me when I described what I was researching, but were kind enough to give the impression I had something useful to offer.

Allow it to shape your research on a fundamental level

In my case, I’d played it safe and requested Times Digital Archive data from between 1903 and 1920. Choosing dates was always going to be arbitrary; 1903-1920 encompasses the period of time from the formation of the Women’s Social and Political Union to two years after the Representation of the People Act 1918 which gave women the vote. If I wanted a lot more data, I could have asked for 1860 – the decade in which the campaign for women’s suffrage emerged out of other social protest movements – to 1928, the year in which women were granted the franchise on the same terms as men. That was too much to take on for a PhD project, and I had to narrow my focus. I could have simply chosen a five or ten year period – say 1910 to 1915 – but this wouldn’t have made sense in the social context of the time.

My research in history quickly revealed that the outbreak of World War One led to a complete change in the suffrage movement; it forced them to engage with nationalism as revealed and understood through warfare. It was also clear from looking at the initial data that the newspaper’s shift in focus and the amount of news they actually printed changed after 1914. Including the years between 1914 and 1918 would therefore change the scope of the project and that was too much to take on for a PhD project. My research into history also gave me a starting year – 1908, on the cusp of suffrage direct action.

The historical background, therefore, played a crucial role in shaping the project and delineating its boundaries.

It’s not just the icing on the cake

Related to the previous point: I didn’t want the historical analysis to be something I only brought into play in conclusions.

This ties in with a corpus linguistics issue of having to know your data in order to do in-depth work with it. If you handed me a corpus from a culture that I know very little about – let’s say, for sake of argument, Arabic literature – I would probably be able to make some pretty graphs and identify some words which behave in interesting ways and which are perhaps worth further investigation, but because I don’t know the history and the context in which these texts operate, I would be unable to connect these interesting words to things that were happening that would affect the discourses. I wouldn’t know about events, wars, peace treaties, rulers and governments, innovations, philosophies, schools of thought, cultural shifts.

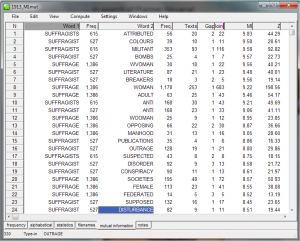

While my work is in (corpus) linguistics – my background is in linguistics, I’m (currently!) based in an English department and my thesis will be examined by linguists – I don’t think I could write a good linguistics thesis using this particular corpus without also writing about history. It’s something I’ve always had in mind when interpreting data – and not just in the sense of “writing about what I’ve observed”. In corpus linguistics, categorising and grouping your data can in itself be a form of interpretation; I found it was vital to understand the historical context in order to come up with meaningful categories. At the moment I’m looking at the news narratives of Emily Wilding Davison’s actions, hospitalisation, death, inquest and funeral procession; these were all reported, sometimes extensively, in the Times. However, a critical discourse analysis approach requires the analyst to be sensitive to what is missing as well as to what is present, and so it is vital for the analyst to be aware of the wider context of the text. This was where an understanding of the historical context is so important. For example, the Times notes that Yates represented Davison’s family at the inquest into her death. A passing comment, perhaps. However, with my knowledge of the suffrage movement, I was able to recognise this man as Thomas Lamartine Yates, husband of one of Davison’s close friends and unofficial WSPU legal advisor. In some ways, this raises more questions than it answers – was he providing his services because of his wife’s association with Davison or does it say something about Davison’s posthumous changing relationship with the WSPU? – but it makes for a richer analysis.

To go with the cake metaphor, I don’t think of my research as a linguistics cake with a tasty history icing. Nor do I think of it as a linguistics and history battenburg cake, nor a linguistics and history marble cake. instead, the two are inseparably mixed.

Be humble

I am not a historian by training. I have undoubtedly made mistakes and been blind to things – interpretations, undercurrents – that a person with 5+ years of intensive study of history behind them would notice. There’s a lot that I don’t know, and if someone asked me to discuss in detail the politics of Empire during this time period or the campaign for equal franchise in the 1920s, I’d struggle. I hope that I’ve been a respectful and sensitive outsider and my work can offer some useful insights to “proper” historians, but I also hope I can accept their inevitable corrections with grace and humility.