Following on from my last post about student mental health, here’s a post from the other side of teaching about making space for “quiet students”. There are some really interesting ideas there and it’s made me reflect on my own teaching practice.

When I was an undergraduate, one of the people I was taught by seemed to have an air of desperation and mute appeal whenever we scrutinised the floor rather than meet his eyes. I found it unbearable; it would make the seminars drag on (dull – I wanted to get to the interesting stuff!) and honestly, I felt kind of sorry for him. So I talked a lot (which I disliked, and disliked myself for not shutting up) but furthermore, I felt I was being forced into the position of the talkative student who risked looking daft just so that the tutor at least had something to build on. I wasn’t a quiet student, but I resented not being given the chance to be one.

When I started teaching, I was determined not to reproduce that dynamic but at the same time, didn’t want to pick on people. I think there’s room for silence as a pedagogical tool but it wasn’t something that I wanted to use on a regular basis. In addition, I knew what access requirements my students had requested; some of these requirements concerned seminar room dynamics.

Instead I got my students to talk in pairs, trios or small groups while I visited each group in turn, listening to what they had to say, encouraging them and making sure they would have something to offer. I then brought the whole seminar group together and elicited something out of each group. I don’t know how obvious it was to my students but everyone got the chance to speak in the seminar and usually did so.

Obviously this tactic wouldn’t work everywhere and in every type of seminar which is why I liked Sarah’s post so much. I also think that strategies for helping quiet students create a better environment for everyone – everyone gets a chance to participate, no one feels vaguely resentful like I did as an undergraduate, and these strategies help make a seminar a supportive environment where students can try out ideas.

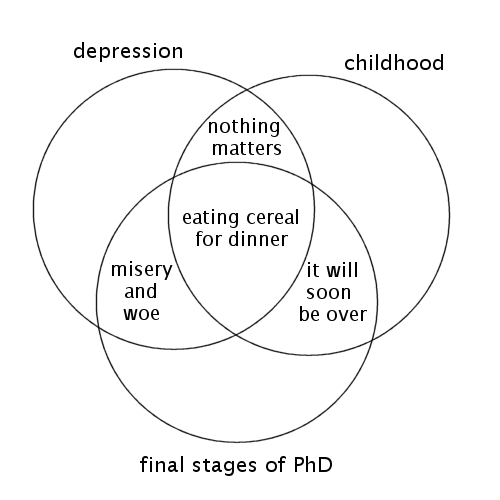

Something I didn’t discuss was mental health as specific to PhD students; this isn’t due to me not caring but, rather, it being a bit too personal. Jessica has recently been writing about this – there’s more in the series, but I particularly liked PhD blues: mental health and the PhD student and Having “the chat” with your supervisor: what I talk about when I talk about depression.

I also like this post about the experience of doing a PhD while disabled or chronically ill and the sheer stubbornness it takes: disabled PhD students of the world unite, unite and take over

And yet our inability to show up has no significant bearing on our ability to contribute beautiful original things to the world. We have the experience of working successfully according to our own strategies: we must do, for how else could we be here, now? We have strategies to get around these walls in our world. We need only your support, your belief, and your acknowledgement that the stories here speak to a state of affairs whose days should be numbered.

In other words: we know how to do this. All we need is the right support, the right conditions. In this respect we are no different from any other PhD student, or any student, or any individual embarking on a project of any kind.

Every single PhD student has worked hard to be where they are. Every single disabled PhD student has had to do this work within a context where things may be harder than they are for your average bear. They are not the only ones. Nonetheless, their experiences represent a distinct category of experiences among many. As with so many things it is only by bringing these experiences before the eyes of the world that we can hope that things will ever improve.