Recently I was in a cafe with a friend who is just starting her PhD. Talk turned to what we were lugging around in our bags: the usual annotated journal articles, academic books, phone, keys, wallet, railcard, pens, notepads…and my organiser. I’m one of those sad people who still uses a paper organiser. To add to that, it’s also a filofax. I am either so very cool no one else recognises my coolness (yet) or I am just a bit of a loser.

I like writing on paper for several reasons. A diary is harder to lose, my style of scribbling in diaries doesn’t lend itself easily to electronic means, I find actually writing something helps me remember it, I like my handwriting and pens and the smooth trail of ink over paper. I don’t like feeling dependent on a phone for all my needs and already feel somewhat over-reliant on it. Laptops are often more cumbersome and heavier than I want to carry around with me all day, a tablet is prohibitively expensive and ultimately, I like having something that doesn’t run on batteries and therefore won’t inconveniently die on me and force me to hunt around for a coffee shop that has a plug point I can borrow.

I like using a filofax in particular because of its flexibility. I can add more stuff, shift the diary from a Jan-Dec to a Sept-July format, rearrange bits within it, and create new sections if I need them. I am also ridiculously fussy about the diaries I use, and when I bought a bound diary each year I would get slightly obsessional about finding exactly the right kind of diary – week to two pages, either faintly ruled or unruled paper, not-hideous fonts, decent quality paper. While the filofax diary inserts aren’t perfect they are at least consistent.

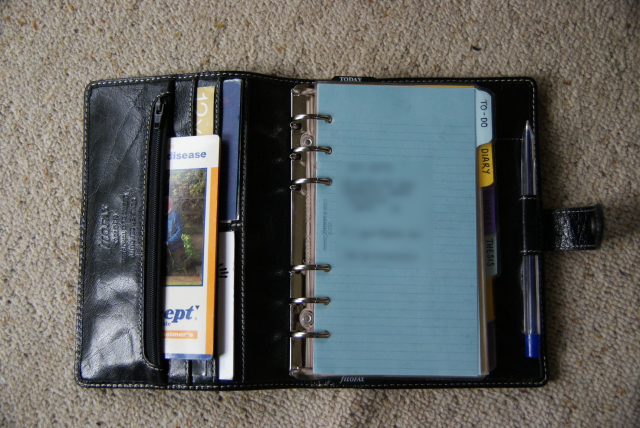

The set-up I have at the moment:

- a page with my name, address and contact details

- a section for my to-do lists

- a section for my diary

- a section of plain and lined paper for general notes

- a section of paper for thesis notes

- two spare sections that I can use for something if necessary

- plastic pocket, card holder and map at the back

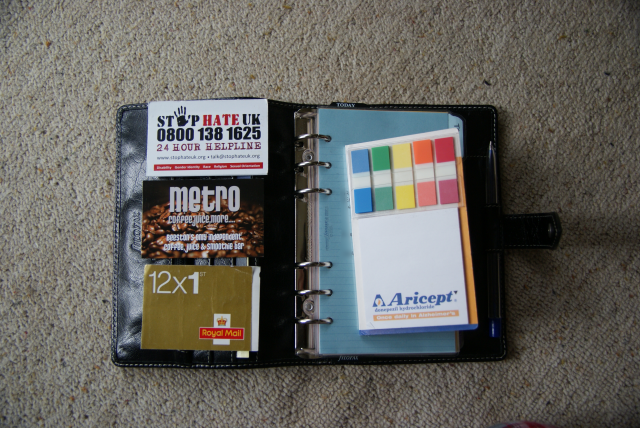

I live in a household of two medical doctors and two academics so we have a good stash of stationery! Perhaps appropriately (or not at all appropriately, depending on your sense of humour), Aricept is used to slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. And therefore, they give out post-it notes to help doctors remember things (like their brand).

I have a front card with my name, permanent address, personal email and phone number. I don’t like the front sheet that comes with filofax organisers as it’s too much detail that I don’t particularly want to share. I made the dividers out of card then laminated them so they’re hopefully durable enough to last.

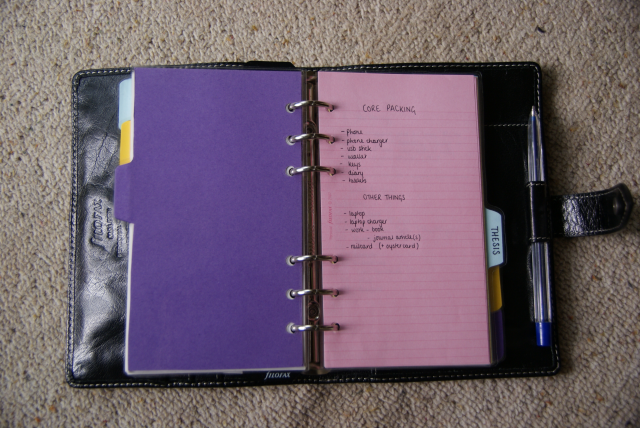

This is the first page in my general notes section and is my “you’re leaving the house in 15 minutes, have you got everything you need?” list. Trust me, it’s not good to have your laptop in one county and your laptop’s charger in another!

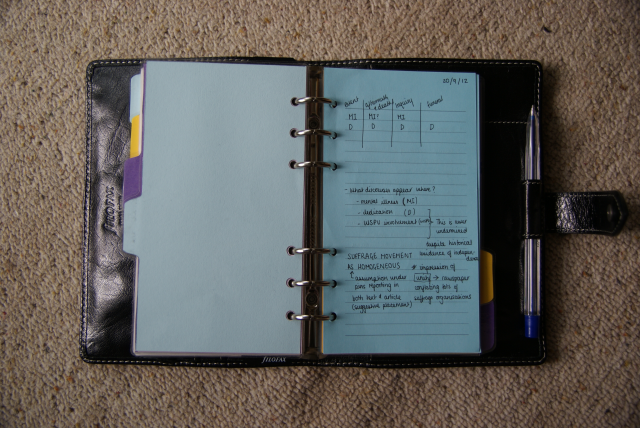

This is the first page of the thesis notes section, complete with scribbly 4am writing. I try not to take my work to bed with me, but sometimes it happens.

You don’t get to see my diary because there’s too much personal stuff in there! I use it to keep track of where I’m supposed to be when – so meetings, research seminars, my various bits of paid work and deadlines as well as meeting up for coffee, reminders to buy cereal, eye appointments and so on. When I’m very busy it’s a relief to be able to write these down and not worry about forgetting them. The downside is that unless I write these down, I forget them.

My organiser is pretty minimalistic compared to some – if you want a look at how other people organise their things, I recommend looking at Philofaxy and particularly their regular Reader Under the Spotlight profiles.