My awesome and fearsomely clever little sister has just started blogging. She researches Active Galactic Nuclei and knows lots of stuff about space, black holes, blazars and ska-punk. She’s also a member of the Jodcast team and has done exciting stuff like interviewing Professor Brian Cox. So yes, read her blog!

Author: Kat

Religion, Youth and Sexuality

Today I went to the Religion, Youth and Sexuality conference at the University of Nottingham. I’ve been closely involved with a the project but not as a researcher – as a participant. I answered a questionnaire which was followed up with an interview, then they deemed me sufficiently interesting to keep a video diary for a week.

It was a really interesting opportunity – firstly, as a researcher, it was a valuable experience seeing how other people in a different field and with a different theoretical and methodological background conducted research. Secondly, and somewhat unexpectedly, it was valuable as a participant. I went into the project thinking that I’d do some people a favour – they needed people to fill out their questionnaire and as a researcher, I like helping other people out with their research. Part of this is blatant and unfettered curiosity, part of this is the acknowledgement that research often depends on people willing to fill out questionnaires and one day, I might be soliciting data in that way. Part of my special interest in this project was the chance to get some representation; I do not see people like me represented in papers or magazines or TV, and perhaps my participation would help address that.

What followed really pushed me into thinking about how I conceptualised religion and sexuality and forced me to examine my beliefs. Sometimes the best way to sort things out in your own head is to talk to someone else; the questions were never intrusive or aggressive but I found myself reexamining things and realising that, for example, no, I didn’t actually have a problem with X but actually Y was a really important issue for me. It made me think through the various inconsistencies and really try to reconcile sometimes very different beliefs and attitudes. I’d grown up keeping these two aspects of my life pretty separate but this was an arena where I could acknowledge these two facets of my identity and how they informed each other, think about the links between them. I wasn’t prepared for how validated this made me feel – not just in terms of acknowledgement and acceptance, but that my daily life was of interest to the research project and worth investigating.

When I volunteered as a participant, I wasn’t really expecting to gain much from it. Instead I found it an interesting and rewarding experience, so much so that I hope they get the funding to following us up in a few years.

Activist linguistics

Activist linguistics, as I see it, does not mean that the researcher skew her or his findings to support one group or one ideology or another. Nor does it mean that a famous linguist use her or his fame to support causes. Rather, an activist linguistics calls for researchers to remain connected to the communities in which they research, returning to those settings to apply the knowledge they have generated for the good of the community and to deepen the research through expansion or focus.

O’Connor, P. E. (2003). “Activist Sociolinguistics in a Critical Discourse Analysis Perspective”. In G. Weiss and R. Wodak (Eds) Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory and Interdisciplinarity. Basingstoke: Paulsgrave Macmillan

This is something I’ve been thinking about.

This is something I’ve been thinking about.

In some ways, my PhD research area is a deeply personal thing. It might be about a social movement and people and events a hundred years ago, but it encompasses areas that I care deeply about: gender equality, the theory and practice of protest, marginalised and disenfranchised groups, the interaction between ideology and practical legislative change. The photo is one of the more visible acts of protest I’ve done recently – it was taken on a cold winter’s morning before I went to London to protest about cuts to arts, humanities and social sciences. That experience led me to write this post.

I worried quite a lot about whether my personal politics would affect my research for the worse. Would it make me too sympathetic, unable to see the flaws in direct action? Would I end up hopelessly over-identifying with the subjects of my research? Would my thesis become a paean to the suffrage movement? Would I, too, end up setting fire to a boathouse? Worrying thoughts indeed.

But now I’ve started wondering about neutrality. Is actual neutrality even possible? I’m not convinced it is; to me it seems that you can simply not know enough about an issue to have an opinion, or that your apparent neutrality is itself a stance. I’m reminded of debates within feminism where those allegedly objective about it are actually hostile – there are some things it’s hard not to have an opinion about, and if you’ve chosen to distance yourself from an issue you’ve still made a choice about how you’re going to engage with it.

As I said in my post on direct action, being a protester has given me an insight into the kind of things the suffrage movement encountered. When I wrote that post it was police violence; as I write now, it’s the tensions between different groups and factions who are (roughly) campaigning for the same things.

As O’Connor suggests, things like this are going to inform one’s research whatever I do and my issue is one of how to allow it to do so, how to acknowledge it and be honest about its influence. There are different ways to engage with one’s activism and individual politics, and it’s clear which she thinks is best. As well as making for better research, I think the researcher also owes something to the community in which they’re embedded. As an undergraduate I was staggered by Jennifer Coates’ admission that she covertly recorded her friends for material. At the time it was an acceptable methodology to make such recordings; now it is most definitely not. I’m not studying NSAFC (if I was I’d tell them!) but that earlier post was still an attempt to apply my research to my community, to give back something – kind of connecting my experience as a researcher with my experience as a protester, and trying to synthesise them in to sort of whole I think O’Connor is talking about.

As a tangent, I stumbled upon Emily Davison Blues by Grace Petrie a couple of months ago. There’s a research paper in contemporary reimaginings of the suffrage movement, I know it.

Okay, I was going to go to bed at least an hour ago. Tomorrow brings more narrative theory and newsworthiness, yay?

Kat vs ebrary

Still ill, much to my annoyance. The only productive thing here has been my cough (ba-dum-tish!)

Anyway, today I tried to do some work chasing up a reference. The library had it (yay!) but only through ebrary (boo!). Every so often I wonder if my resistance to ebrary is because I’m being a luddite and refusing to use something that will make my life much easier. Then I actually have to use ebrary and realise that no, I’m entirely justified in this.

The above screenshot shows what it looks like on my monitor. I am deeply puzzled as to why the contents page needs to take up so much of the screen, leaving the text itself cramped to one side.To me this seems counter-intuitive – after all, I want to read the text – but what do I know, I’m only a researcher.

I am also puzzled as to why their top menubar doesn’t move as you scroll down the page:

You either have the choice of making the text bigger and easier to read OR having to scroll up every time you want to turn the page. It’s tedious.

In conclusion, I don’t think it’s reading a book through a web interface that makes me cross, it’s the peculiar and inflexible design decisions that are making me cranky. Digital and online interfaces are all well and good, but good, thoughtful design is so important to make them usable.

(and yes, I’ve checked Google Books (the chapter I want isn’t available) and I’ve checked Amazon (the book’s £88 and there doesn’t seem to be a paperback). If there was an alternative less annoying than ebrary, I’d use it.)

My tools

Recently I’ve been going to bike maintenance workshops. It’s been an interesting and often satisfying experience. There’s the comfort of knowing how to check your own bike for damage, how to mend punctures and how to be a more self-sufficient cyclist. There’s also a sense of satisfaction about doing something that has physical results, something that gets you covered in bike grease and dirt, something that requires you to work with your hands as well as your mind.

There seem to be a few books out discussing the issue of working with one’s hands and the dangers of office work. It’s hard to write about this without romanticising manual work from a smug, clean fingernailed, academic stance, from the privileged stance of this being a choice for me, of this being as unnatural for me as Marie Antoinette playing milkmaid at her hameau.

However, for me at least, there’s also a sense of responsibility; if I use something every day I should be able to understand how some aspects of it work, be able to fix some problems, know when I’m out of my depth. It gives me a better understanding of my tool’s capabilities and limitations. Does it make me a better corpus linguist? In some ways, yes – I built my desktop myself to a specification I designed for corpus linguistics. It’s skewed towards processing power and data storage, and light on the graphics. In other ways, not yet. While a computer is a bit more than a magic box for me, there’s still so much I don’t know about what it can do and how it works. The more sensitive I become to how computers work, what they’re capable of, what they are incapable of, and the implications these have for investigating language use…well, it can only be a good thing, right?

Bit of a ramble I’m afraid, I’ve caught some horrible student lurgy and am feeling a bit fuzzy-headed.

Obligatory pet post

I am aware that the internet likes cats, so here’s hoping that it also likes rats. I am led to believe that Pebble dictates posts to an obliging Knotrune, but my rats, in true academic style, are unable to reach consensus on anything (except possibly that yoghurt drops are worth squabbling over and sundried tomato is foul, evil and proof that no one loves them).

Anyway, today I had a productive day of sitting around looking helpful at the LGBT History Month display, attending a workshop on procrastination (ready for the inevitable comment of “no, I wasn’t putting it off”? Good), being interviewed by Andy Coverdale and coming to the conclusion that I really need to get one of these things commonly known as “a life”. Upon my return, I found that the darling ratcreatures had also been busy…

What you see there is a nice, new hammock made by Fuzzbutt Cage Comforts. At some point today, the rats chewed a hole in the fleece, then proceeded to fill the hammock up with cardboard bedding. Just…why? The way the cage is set up means there’s clambering and jumping involved to get into the hammock, the hammock is quite full of bedding, and they must have moved the bedding one mouthful at a time. Full marks for effort but just…why?

Incidentally, this is usually the kind of photo I take…

I’m trying not to dwell on the sheer futility of their actions because it will only encourage me to draw a comparison with my own life of writing a 80-100,000 word thesis maybe four people will read. Much like the rats climbing up the bars and rope to tenderly deposit their carefully gleaned mouthful of bedding, only to scurry down again in a cycle that must have lasted Quite Some Time. Only their actions might result in a comfy bed, and mine won’t. Carry on, ratlets. I am in no position to judge you.

A footnote

LGBT History Month starts tomorrow, and perhaps fittingly I read this footnote a few days ago.

Rosen 1974, footnote on page 209 regarding Christabel Pankhurst’s sexual and emotional relationships:

Christabel may well have been a Lesbian, but the evidence is circumstantial rather than explicit: she never married, and the copious documents relating to her life and career do not allude to any heterosexual involvements. All the available evidence indicates she had stronger emotional attachments to women than to men, and the markedly dominant/submissive character of her relationships with Mrs Tuke and Annie Kenney certainly seems to resemble the psychology of many Lesbian relationships. There is, however, no reason to believe that Christabel’s affection for Mrs Tuke and Annie Kenney ever involved conscious sensuality, and as far as the history of the WSPU is concerned the exact nature of Christabel’s sex-life is less significant than the fact that by 1913 she had grown into a state of mind in which she was completely adverse to any form of co-operation with men.

I find it an interesting footnote for several reasons: the first and perhaps most immediately obvious reason is the speculation as to the dynamics of lesbian relationships. Without further information it’s difficult to say whether this observation has anything to do with the perceived dynamics of butch/femme relationships, but I do find it interesting that lesbian relationships are markedly dominant/submissive, and heterosexual ones are not marked in the same way.

Secondly, it was published in 1974; academic research also has a historical context. 1967 marked the passing of the Sexual Offences Act and the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK, and this book was published seven years after that. I don’t want to read too much into a single initial capitalisation, but Lesbian suggests something about how that identity was conceptualised – as something static, as something still close to criminalisation and pathology.

Thirdly, as my last post discusses, there’s a transience in how sexual identities are understood. Our understanding of lesbian identities have already changed between Rosen’s 1974 comment and as I write this in 2011 – I think there’s a belief now that same-sex relationships are more equal than heterosexual ones. There’s more understanding of asexual identities and what these can encompass – grey-A, demisexual, homoromantic. But the context, as well as making it difficult for us to understand an individual’s sexuality in our terms, also affects how an individual would have expressed their sexuality. While sex between women was not a criminal offence, it’s not hard to imagine that the early 20th century was not the most lesbian-friendly of times.

Fourthly, I like how it delivers what Dr Lesley Hall describes as a “codslap”. This footnote reads like a response to others’ speculation as to Christabel’s sexuality, and ultimately concludes that whatever her sexuality, it’s less important than how she felt about men being involved with the WSPU campaign.

For me there’s a tension between the importance of acknowledging historical figures’ non-heterosexual identities when we have evidence for them – people like Alan Turing and Edward Carpenter – and not trying to ascribe sexual identities where there isn’t (enough of) that evidence. Short of necromancy or the loan of a TARDIS, we can’t actually know, and besides, sexuality is just one facet of a person’s identity. Other facets exist and may be more important to that person, and perhaps it’s an issue of finding a balance between sexuality being invisiblised and sexuality overshadowing other important parts of an individual’s identity. It’s something I’m still mulling over though, and I definitely don’t have anything conclusive to say.

If you’re a University of Nottingham person, we’ll have a history display in the Portland Atrium tomorrow between 10 and 4 so come along if you want to learn something about LGBT history.

PS if you do have a TARDIS, I have an interesting research proposal for you…

Queering the Museum

LGBT History month is coming up in February, and, in need of a bit of inspiration, I decided to see this exhibition at Birmingham Museum. I’m a bit of a museum geek and part of what interests me about them is who decides and how they decide what goes on display and how these objects are arranged. Some museums try to tell you a chronological story, leading you through different time periods and artistic movements. Some, notably Cairo museum, group similar objects together: sarcophagi there, canoptic jars here, animal mummies down the corridor there. However, curation is not a neutral act; it can support and/or create hetero- and gender normative interpretations of history, art and artefacts. In this exhibition, artist Matt Smith aims to disrupt these readings.

The museum’s description of the event states:

What happens when we stop thinking the world is straight? Through omission and careful arrangement of facts it is easy to assume that the objects held in museums have nothing to do with the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.

In a bold new project, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, in conjunction with ShOUT! Festival, has allowed artist and curator Matt Smith access to their collections and galleries to tell the stories that museums usually omit.

Museums are expected to reflect society and culture. They make active choices about what is kept for posterity and how it is described and displayed. Turning the traditional on its head, a queer eye has been cast over the museum.

Objects have been rearranged and brought out of store and new artworks have been specifically commissioned to uncover, draw out – and on occasion wilfully invent – the hidden stories in the Museum’s collections.

I think the idea is brilliant and I wanted to like it, but its implementation left me rather less dazzled. Queering the Museum isn’t a separate exhibition but is incorporated into the main displays. I approve of this idea in theory – after all, why should queer history be yanked out of context rather than embedded in more mainstream histories? – but in practice, this made it hard to actually find the queered displays. Unfamiliarity with the museum’s layout and a lack of maps didn’t help.

Some of the exhibits were striking. I liked Jacob Epstein’s ‘Statue of Lucifer’, a statue with the body of a man and the face of a woman, queered by holding a cape of green carnations. The green carnation was used as an underground signifier of sexuality by gay men, and indeed lends its name to a book used in the prosecution of Oscar Wilde. Using it was a play on history and hidden histories, of the tension between overt and covert signs; the visitor, if zie understood the significance of the green carnation, is allowed an insight, the thrill of knowing something other people don’t, the pleasure of being able to interpret an artwork in a way not afforded to others. It makes the viewer complicit in the art, and in doing so, reminds zir of the danger possessing such knowledge could have posed. Of course, I then noticed the information placard by the piece explaining the significance of the green carnation.

Other pieces seemed more humorous – figurines of men cruising, or two women with affectionately linked arms (wasn’t totally sure about the butch-femme dynamic in this though). There was an element of playfulness there that I appreciated, and which also served to challenge the perceived seriousness of the museum. I also liked Smith’s technique of creating stylistically similar objects and juxtaposing them with the “real” artefacts – a creative way of not only drawing attention to his pieces, but also inviting the viewer to question the artefacts around them and wonder about their history.

However, other things didn’t really do it for me. One of the things that disappointed me was the lack of bi and trans visibility. These are identities that struggle to be represented in general – a museum exhibition purporting to make the lesbian, gay, bi and trans community visible shouldn’t contribute to this invisibility. However, as noted, it was difficult to locate all the pieces so they may well have been present. This presented another issue: the difficulty in simply finding the pieces seemed to underline how invisible queer history can be in museums – completely the opposite of the artist and museum’s intentions.

I also wasn’t sure about the static understanding of (homo)sexuality that seemed to be presented. For me at least, part of the fascination of queer history is the different ways sexuality has been understood – I think we do an injustice to people if we try to force the way they understood their sexual identities into the way we might interpret their identities. To give an example or two: would an 18th century assigned-male-at-birth cross-dresser still identify as a cross-dresser if zie was born today and had the option of sexual reassignment surgery? Would James Barry have presented and lived as a man if medicine was a career open to women? Such examples can be described as queer – they challenge the mainstream – but are they LGBT?

Overall, it was something I very much liked the idea of, but was less convinced by the way it was enacted. I don’t think it’s an idea to give up on altogether, but perhaps queering the museum and giving voice to different, secret histories also needs a diversity of people behind it.

creating a history

I don’t remember where I first came across the suffragettes. I was an avid reader as a child, the sort whose parents attempted to ban reading at the table because their beloved offspring would become so engrossed in a book they’d forget to eat, and the sort whose parents were thwarted in this ban when their beloved offspring would read sauce bottles and milk cartons and cereal packets pointedly and out loud. I had certainly come across them by secondary school, and I remember being frustrated when my GCSE history textbook contained a few pages on the suffrage campaign but it wasn’t on the syllabus.

The textbook had the sort of information you’d expect – women chaining themselves to the railings, suffragettes, an image of a poster of a large, evil-eyed cat with the limp, helpless body of a long-skirted woman in its month, photographs and a short case study of Emily Wilding Davison at the 1913 Derby. It wasn’t much, but I was fascinated.

Some ten years later and I found myself actually researching the suffrage movement. In some ways, not studying the movement as presented by my GCSE textbook was perhaps beneficial; it meant I had fewer preconceived ideas about the movement. The more I read (and continue to read), the stranger the focus of that textbook appeared. Why the focus on women chaining themselves to railings, when my reading suggests that was a fairly minor part of suffrage activities – things like large demonstrations, deputations and window-smashing seem more prevalent both in the literature and in the texts I’m studying? Why the focus on the Women’s Social and Political Union rather than reflecting the diversity of the movement and the myriad groups involved? And why the consistent use of the term suffragette, rather than the more inclusive term suffragist?

It’s remarkably persistent too – I’ve lost count of the times people have asked me if my research focuses on these popular representations of the suffrage movement, and I’ve had people email me back to ask if I meant to write suffragette instead in my abstracts. I don’t think it’s a lack of interest – far from it. People seem intrigued by the movement, its actions and figures within it. This event, called “Remember the Suffragettes: a Black Friday vigil in honour of direct action” was held in November 2010 and clearly acknowledges suffragette direct action and its consequences.

I don’t have answers about why this simplified portrayal of the suffrage movement exists, why the Pankhursts and the WSPU and women chained to the railings linger in people’s memories and have this resonance. The cynical feminist in me says that we like our women feisty but not dangerous, that chaining oneself to railings is provocative yet non-threatening, that we are more comfortable with women’s martyrdom that we are with their bombs and arson. We like equal rights and are a bit shocked that women couldn’t vote less than 100 years ago, but we’re a bit scared by what it might take to attain those rights. We’d rather hear about action and grand gestures than endless rounds of legal and political debate and scrutiny. My thinking here is almost certainly simplistic, but I rather suspect that our focus on these particular aspects of the suffrage movement (and neglect of others) says more about our concerns than theirs.

swearing with Google ngrams

Back, after an unwelcome hiatus. I’ve learnt my lesson though, and will be backing my wordpress database up. Regularly.

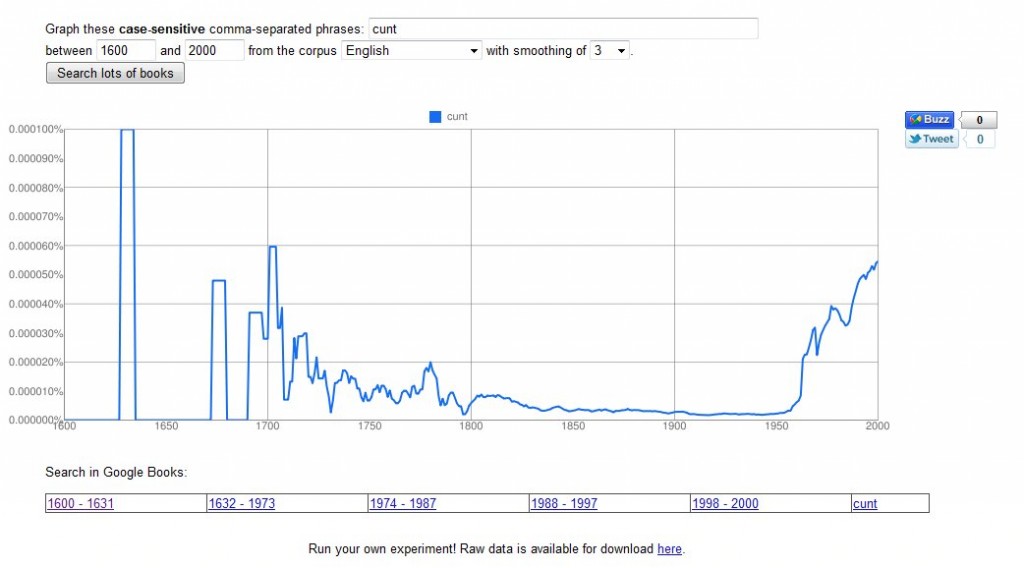

Anyway, being a linguist of the sweary variety, I was intrigued to see someone on twitter use Google lab’s ngram viewer to look at cunt and express surprise and delight that cunt was being used so frequently rather earlier than expected.

I thought the graph looked interesting. The frequency of cunt was rather erratic: an isolated big peak in around 1625-35; an isolated smaller peak in around 1675; peaks in 1690ish and 1705ish; a rather spiky presence between 1705 and 1800; then fairly consistently low frequency until around 1950 when its frequency increases again.

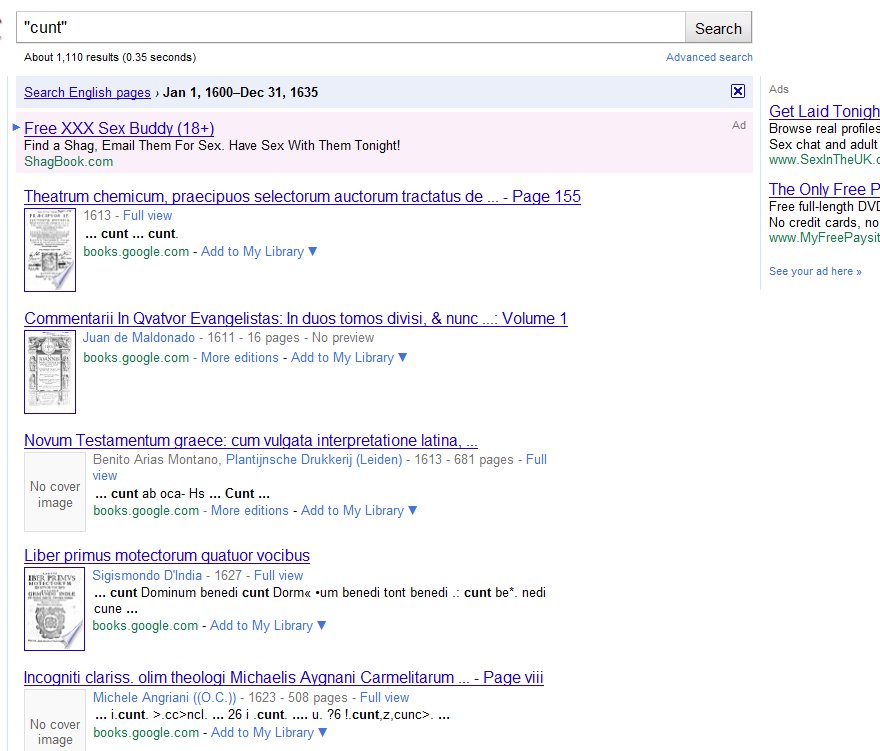

This seemed puzzling – rather than being fairly low-level but present, there were these huge spikes in the 17th century. I decided to have a look at the texts themselves. These turned out to be in Latin, and the following image rather neatly illustrates the two different meanings at work here:

The books themselves seem to be religious texts written in Latin, even if Google’s ever-helpful advertising algorithm seems to interpret things rather differently. As you can see in the first image, I selected texts from the English corpus. It’s possible that the books are assigned a corpus based on their place of publication, but it’s not very intuitive.

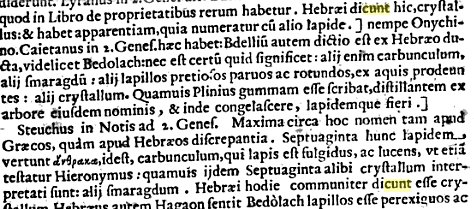

I took a closer look at the texts to try and work out what was going on. Some of the texts were in Latin, as this example taken from De paradiso voluptatis quem scriptura sacra Genesis secundo et tertio capite:

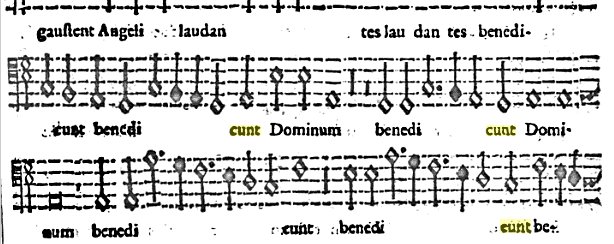

However, this was not the only issue. I found at least one example of a musical score – this example taken from Liber primus motectorum quatuor vocibus:

Here, the full lexical item is benedicunt. In both of these examples, cunt is not a full lexical item; I can understand why the layout of the score might have led to it being parsed as a separate item, but I’m a bit confused why the same seems to have happened with dicunt.

The high frequency of cunt can also be attributed to Optical Character Recognition (OCR). Basically, the text is scanned and a computer program tries to convert the images into text. This has varying degrees of accuracy – it can be very good, but things like size and font of print, the paper it was printed on and age of the texts all have an effect. The text obtained through scanning with OCR is then linked to the image.

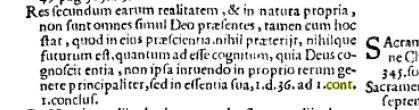

This example, taken from Incogniti clariss. olim theologi Michaelis Aygnani Carmelitarum Generalis, is probably familiar to those working with OCR scanned texts. The text actually reads cont. but the OCR has read it as cunt. The search program can’t read the image files; all it has to go on are OCR scanned texts. When these aren’t accurate, you get results like these.

I think Google ngram is interesting, but with some caveats. Corpora can be tiny – the researcher can have read every single text in their corpus and know it inside-outside. Corpora can be large and highly structured, like the British National Corpus. Corpora can be large and the researcher doesn’t need to have read every single text contained in them, but through careful compilation the researcher knows where the texts have come from, where they were published and so on – for example, corpora assembled through LexisNexis. This is a bit different – it’s not really clear what’s even in the collection of texts and the researcher has to trust that Google has put the right texts in the right language section. I’ve seen Google ngrams being used to gauge relative frequencies or two or more phrases, but for now I think I’ll stick to more traditional corpora for most in-depth work.

Mark Davis also has a post comparing the Corpus of Historical American English with Google Books/Culturomics. His post is in-depth, interesting and systematic; I just swear a lot. You should probably read his.