Trigger warning: this post contains slurs for race, sexuality, disability, neurodiversity and gender.

So I tweeted something the other night and was a bit surprised that it took off:

#confessyourunpopularopinion usually I like political correctness because most of the time it translates to not carelessly hurting people

— Kat Gupta (@mixosaurus) August 7, 2013

As a queer, Asian, female-assigned-at-birth person with an interesting medical history, I like political correctness. Political correctness is why it is generally considered unacceptable to loudly inform me that I am a “chink”, a “paki”, that I should “fuck off back to where [I] came from”, that I should “fuck off back to Santa’s grotto”, that I am a “fucking dyke”, that I am a “fucking lesbian”, that I am a “fucking dwarf” or that I’m an “it”. Obviously not everyone agrees, which is why all of these examples are taken from real life.

When I come across a written article that uses slurs, I am not inclined to read it. I have lots of things to read: my “to read” list is constantly full of books, journal articles, blog posts. Unless someone has contracted my services as a proofreader or copyeditor, I am not obliged to read anything – and I am not wasting my time on something that uses hurtful language. I am not obliged to “look past” those slurs when those slurs hurt me.

If someone who doesn’t have the right to reclaim the term uses the word “tranny” throughout an article, I also have to wonder how far their knowledge extends. As someone who is involved with trans* welfare, health and legal issues, I have to wonder what I can take from it. I read a lot of those articles because one of my academic interests is the media representation of minority groups and issues, but – please forgive me if this sounds arrogant – I tend not to find something interesting and insightful and useful in such articles.

I love words. My degrees have basically been a love affair with words – how they’re used, what they mean, how they come with associations and connotations. I’ve also been accused of being “politically correct” and I’m well familiar with the argument that such political correctness stifles free expression and is a form of censorship. However, I think avoiding these slurs makes me a better, more thoughtful and more creative writer. For example, when I see the word “demented” being used, my mind flashes back to the dementia ward and day hospital where my mum worked and where my sister and I would accompany her if we were off sick from school. I think of my friend’s dad – my mum’s patient – and having to pretend to be my mum because he couldn’t recognise that I was a different person and trying to explain to him that I wasn’t my mum would be pointlessly upsetting. I think of the astonishing people my mum has treated – doctors and teachers and lecturers and footballers – and their families, and the aching loss of a mind, a history, a person.

I almost certainly don’t think what the writer wants me to think, which appears to be “isn’t this insane[1]/outrageous!”.

If I wrote something and there was so great a mismatch between what I wanted to say and what my readers took away from it, I’d consider that an unsuccessful effort. Not because I’d upset someone – I enjoy creating discomfort and disquiet in my creative work – but because I’d upset someone without intending to, because I’d used my words ineffectively, because it meant that I wasn’t doing my best as a writer.

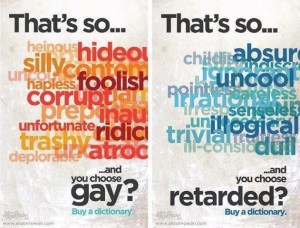

Being politically correct has made me think about my language choices, and to think carefully about what I want to say. I’m reminded of these posters by Alison Rowan:

There are lots and lots of alternatives which often express something more precisely. Just look at what you could use instead of “gay”: silly, heinous, preposterous, contemptuous, hideous, hapless, uncouth, unfortunate, deplorable, trashy, ridiculous, atrocious, corrupt, foolish. Or “retarded”: childish, absurd, indiscreet, ignorant, uncool, pointless, careless, irrational, senseless, irresponsible, illogical, unnecessary, trivial, ill-considered, dull, fruitless, silly. Each of those has different shades of meaning. Instead of the scattershot of “retarded” or “gay”, your words can be like precision strikes, hurting only the people you intend to hurt.

If you want to hurt people, that is. How much worse it is if, in your casual and unthinking use of “gay” or “retarded” or “spaz”, you wound someone you never meant to wound, never realised you wounded.

So back to political correctness.

The term “political correctness” was popularised by its opponents; people who agree that political correctness is often a good thing tend to call it other things, like “basic courtesy”. Political correctness means treating people with respect and courtesy, being mindful of what they do and do not want to be called and how they do or do not want to be addressed. It is offering dignity to minority groups, who are already being shat on in so many ways without having to deal with a barrage of slurs.

Saying that you’re against political correctness is not radical or edgy or subversive; it affirms the status quo. It affirms society’s default as white, straight, cisgendered, neurotypical, non-disabled, male. It does not challenge or mock or destabilise power. What, precisely, is subversive about trotting out the same tired racist, misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic, ableist crap?

[1] And let us contemplate the wide variety of words used to stigmatise mental illness and neurodiversity.