[content warning: discussion of homo-, bi- and transphobia, racism, domestic abuse and suicide. I’ve tried to keep these fairly non-explicit; the reports I link to go into more detail]

This is a write up of a short talk I gave at the final conference of the ESRC seminar series ‘Minding the Knowledge Gaps: older lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans lives’. The organising team and I have been having an involved discussion since my first post and they were kind enough to invite me to speak as part of the summaries of previous events.

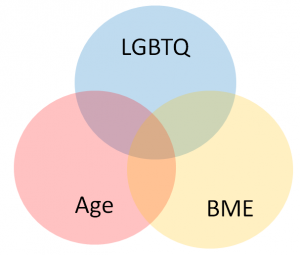

In this talk I discuss lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) identities, Black and minority ethnic (BME) identities and ageing identities. I ask what it means to live at the centre of these overlapping identities and look at how we can extrapolate some issues from what we know about overlaps of age and LGBTQ identities, age and BME identities, and LGBTQ and BME identities. However, this is by no means a perfect solution because it misses that complex intersections bring their own unique issues – there is effectively a known unknown about the experiences of older LGBTQ people from BME backgrounds, and I want to highlight that.

Intersectionality

Very basically, intersectionality is the concept that we have multiple identities and that these identities overlap and inform each other.

Here’s a diagram to show these intersections a bit more clearly.There are three coloured circles: a blue circle representing people’s LGBTQ identities, a red circle representing people’s identities as older people and elders, and a yellow circle representing people’s BME identities.

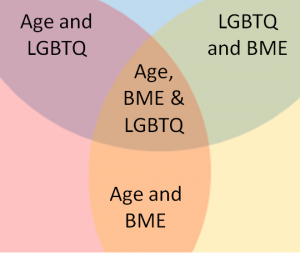

When these identities overlap, they create something new. The purple overlap shows the interaction of ageing and LGBTQ identities, the green overlap shows the interaction of LGBTQ and BME identities and the orange overlap shows the interaction of ageing and BME identities. At the very centre is a space where all three factors interact: age, LGBTQ and BME.

We don’t know much about the people who occupy this really complex space. Roshan das Nair talks about “levels and layers of invisibility” and of each factor – age, sexuality and race – all contributing to invisibility. However, intersections change the experience of “being” – of accessing care, of forming relationships with other people, of moving through and understanding (and being understood by) the world. As this seminar series has strikingly shown, being an older LGBTQ person is not the same as being an older heterosexual and cisgender person. And being an older LGBT person from a BME background is not the same as being an older LGBT person from a white background

LGBTQ and BME

While there is a paucity of information on the unique issues faced by older LGBTQ BME people, there is research on ageing LGBTQ people as showcased in this seminar series, on BME LGBTQ people, and on ageing BME people.

Two current projects highlight some of the issues for people who are both BME and from sexual and gender minorities. A Public Health England report on the health and wellbeing of BME men who have sex with men highlighted that:

- Black men who have sex with men are 15 times more likely to have HIV than general population

- a third of Asian men and mixed ethnicity men have experienced domestic abuse since the age of 16 compared to one in five of white gay and bisexual men

- significantly higher rates of suicide, self-harm and mental illness

A recent focus group held by the Race Equality Foundation on the experience of being black and minority ethnic and trans* highlighted that people experienced:

- religious communities overlapped with ethnic communities, and losing one often meant losing the other

- racism in LGBT communities and homophobia, biphobia and transphobia in ethnic communities

- cultural assumptions and racism when accessing healthcare

The last point had particular repercussions for Black and minority ethnic trans people seeking to access hormonal and/or surgical interventions for gender dysphoria through Gender Identity Clinics (GICs). Respondents to the Trans Mental Health Survey often found it difficult to access treatment through GICs, with one respondent describing it as “a paternalistic gatekeeping exercise where psychiatrists exercise inappropriate levels of control over the lives and choices of patients”. Another described clinics as having “very rigid ideas of masculinity and femininity”. This affects Black and minority ethnic people if genders in their culture do not map onto gendered expectations in white UK culture. BME trans people also encountered assumptions about family (for example, what does “being out to your family” look like if you have a huge extended family or if “kinship” doesn’t neatly map onto “family”?), assumptions about transphobia in their families, and poor understanding of non-binary genders.

Age and BME

Research on older BME people tended to show that people were affected by health issues occurring at different times (e.g. diabetes and high blood pressure). Black and minority ethnic people may have complex issues around mental health and accessing services. Some communities may stigmatise mental health issues. African and Caribbean men are “under-represented as users of enabling services and over-represented in the population of patients who are admitted to, compulsorily detained in, and treated by mental health services”. As this report on older South Asian communities in Bradford discusses, how families live together is changing. However, there is still an expectation that the extended family will care for elders; this role often falls to younger women in the family. This study also reported that South Asian communities often found accessing care difficult for a huge range of reasons – cultural differences, a lack of cultural competency in service provision, language difficulties, attitudes of staff, differing expectations by both service users and service providers, location of services, gender roles within the family and the role of different children and siblings.

It is also important to recognise the diversity of BME experiences. There are some BME communities that have been settled in the UK for decades, if not centuries. There are South Asian people who migrated to the UK as young adults in the 1970s and who are now reaching retirement age. There are older people who accompanied their family members. There are more recent immigrants. There are people who live with the trauma of fleeing their home and seeking asylum. The term “Black and ethnic minority” itself covers a huge range of people from all over the world, all with different experiences.

Extrapolations

As I wrote earlier, there are going to be known unknowns – without talking to people, we cannot know about the unique, unexpected issues created when identities intersect. However, I think that the research on LGBTQ and BME communities, the research on older LGBTQ people, and the research on older BME people can hint at some issues.

Older LGBTQ people report different kinship structures, the existence of chosen families and possible lack of children. I wonder how this works for older BME LGBTQ people whose cultures may strongly support care of elders within the extended family (and who dislike the idea of care homes or care workers coming into their homes) but who may be estranged from their family and don’t have children.

I can imagine that there are really complex issues around mental health in communities that are more likely to experience mental health issues but who may also have negative experiences of accessing services or who may feel shame about doing so.

Older BME LGBTQ people may have complex histories of violence. As Public Health England reports, gay and bisexual men from BME backgrounds are more like to have experienced domestic abuse. Other BME LGBTQ people may have sought asylum due to violence in their home countries. What might their care needs be?

I wonder about older BME LGBTQ people continuing to face racism in LGBTQ spaces and homo-, bi- and transphobia in BME spaces as they age and these spaces change. This seminar series has discussed older LGBTQ people’s fears about prejudice in care homes; older BME LGBTQ people in care homes may fear a double whammy of prejudice.

Where are our elders?

I argue that there is an absence of older, LGBTQ BME voices in research about older LGBTQ people’s experiences. As researchers, we don’t know much about the issues faced by those in this intersection – as I’ve shown above, we can guess some of them. However, the nature of intersectionality means that there are some issues that will be unique to this group and that we cannot predict.

This is not to say that older BME LGBTQ people do not exist – rather, that we have to do better at reaching out to these communities. I suspect that research into the experiences of older BME LGBTQ people has to be carried out by people from BME LGBTQ backgrounds. My experience of younger BME LGBTQ spaces is that community members are fiercely protective of the tiny spaces they are able to carve out for themselves and they do not want to be observed as a “learning experience” for White straight cis people. It is crucial to recognise that, and crucial to be able to respect how rare and precious these spaces are.

This absence of visible older, LGBTQ BME voices also has implications for younger BME LGBTQ people. Out of the many trans people I know, I can only think of three who are BME and over the age of 40. 40 should not be considered old – and yet. A US study reveals that the attempted suicide rate for multiracial transgender people is 33 times higher than for the general population. Andre Lorde’s litany, “we were never meant to survive”, has a heartbreaking resonance.

As a younger Asian queer person, I want to meet my elders. I want to know that it’s possible to be an older BME LGBTQ person. I want to be able to see some of the possibilities, to see that there are people living lives that are true to their identities. I want to listen to their rich histories and hard-won wisdom. I want to know that we can survive.

Our elders are so important, and their lack of visibility is so sorely felt.